Harvey Weinstein’s assistant Rowena Chiu: I was silent about my harassment for 20 years because I was afraid for my family’s safety

Rowena Chiu, former assistant to Miramax CEO Harvey Weinstein, was sexually assaulted by her boss in 1998. After 21 years of silence, she spoke about her experience in 2019 and became one of the spokespersons for the MeToo movement. Her story became known to a broader audience in an opinion piece written for the New York Times, and the incident was featured in the film “She Said” that was released in 2022. Singapore-based gender equality consultant Pirjo Turk interviewed Chiu. In the following interview, cultural background in the context of sexual violence, the complexity of harassment processes and the importance of sharing experiences will be discussed.

Rowena Chiu is a management consultant with Chinese roots, raised in England and now living in California. In 1996, she graduated from Oxford University with a degree in English Literature and was president of the Oxford University Drama Society during her studies. She had dreamed of success in the film industry. In 1997, she was pleased to get a job at Miramax’s London branch as an assistant to Zelda Perkins, Weinstein’s personal assistant. Perkins warned Chiu during the job interview that her potential new boss was known for his inappropriate behavior and violent temper tantrums. Yet, nothing would happen if he was “handled vigorously.” In the fall of 1998, when Chiu was 24 years old, she was at the Venice Film Festival as Weinstein’s assistant. Weinstein habitually invited employees into his hotel room to discuss business, often late at night. He also invited Rowena to a late-night script discussion. Weinstein asked her to massage him (it is later revealed that he asked many of his victims to do this), and before Rowena managed to escape, Weinstein pushed her against the bed and pulled off her pantyhose.

Many sexual assault survivors don’t tell anyone, maybe not for months or years.

Shortly after the shocking experience, Chiu told her colleague and supervisor, Zelda Perkins. Perkins became so angry with Weinstein that she and Chiu tendered their resignations to Miramax. Returning from Venice to Miramax headquarters in London, they hoped that telling management what had happened would lead to Weinstein’s firing. Unfortunately, this was not the case. They were instead pressured to sign a non-disclosure agreement (NDA), which meant that they were not allowed to tell not only family and friends but also doctors, therapists and media outlets, including ones that didn’t exist yet. However, at the insistence of Perkins and Chiu, the contract included clauses intended to protect the women from Weinstein’s behavior. For example, the contract included a requirement that Weinstein undergo therapy to recover from his sexually aggressive behaviour; Weinstein had to leave Miramax if he crossed the line again and tried to cover it up; Miramax agreed to a complete overhaul of its HR practices, establishing safeguards for employees, including a three-tiered reporting system for sexual harassment or assault at work. In retrospect, these claims were useless because there was no oversight, and the victims had to remain silent, so Weinstein continued as before.

Chiu remained silent for over 20 years, fearing for her family’s safety. To keep Perkins and Chiu quiet, Weinstein had hired them to monitor Black Cube, an Israeli spy agency staffed by former Mossad agents.

Rowena Chiu. Foto: Kathy LaBarre

You mentioned that you did not tell your loved ones about what happened in Venice, not only because of the NDA but also because of your Chinese roots, where you don’t discuss such personal matters. Could you please explain more about how Chinese culture is different from Western culture in that sense?

Generally speaking, sexual assault survivors don’t immediately come off as a sexual assault. Regardless of my culture, even though I was Asian, I wouldn’t say that my immediate reaction was that unusual. I told three people, which I think is a lot. Many sexual assault survivors don’t tell anyone, maybe not for months or years. Because of the sense of shame, but also because what happened seems unreal, and I think that women tend to question themselves – did that really happen? was it my fault? etc.

Harvey liked to control people’s personal relationships and I think that is one of the main characteristics of an abuser.

There can be many complicated reasons why a survivor won’t immediately talk about their experience and I believe that to be true regardless of cultural backround. I told Zelda Perkins, who was my colleague, the following morning. And as I’ve mentioned in several interviews, my intention when I went to tell Zelda was not to complain about what a horrible thing happened to me, please help me, can we go to the police – although that is how she interpreted it. I told her, because she was my colleague, and she had trained me in everything about this job and I felt that I had done something wrong, that did not prevent an assault like this. So I asked her more in a work context. Of course, I was very upset about what had happened – as she saw, I was crying and in shock, but I had not anticipated that we would go to the lawyers or police. I was more prepared she would say: “oh, you silly girl, you know, this is how you should have managed it”. But obviously, her reaction was much greater than expected – we both ended up resigning our jobs, going to the lawyers and police. She was the first person I told. But as I was in Venice, and still far from home, this is not a piece of information you would text someone, so when I got back to London, I talked to my boyfriend. This happened before the NDA.

People think that the very next day after the assault, we got sealed by an NDA. Well, that’s not technically true. It took a while, six weeks, because obviously, Harvey thought we wouldn’t react that way. So it took a while for us to go to more senior people than us in the office to ask for advice. As they weren’t willing to help us, we went to lawyers, and then it took a while to get lawyers. When Harvey figured out we were serious, he flew over and he negotiated the NDA and then we got sealed into silence.

Rowena Chiu. Foto: Kathy LaBarre

But obviously, I told my boyfriend, best friend and two colleagues about what happened. It is often said that you had to make up the story unless you told someone. If you didn’t tell anyone, there’s no proof it happened. By now we know a lot about the trauma associated with sexual abuse, and it is very, very common for people who have been sexually abused to not tell anyone at all.

I want to say that I was an ordinary 24 year old, pretty extrovert and sociable and I did have a normal life until I fell into depression and made two suicide attempts…I had a boyfriend and a close circle of friends, but over time Harvey took all of that away and those relationships eroded. It was very typical of Harvey to control personal relationships. For example, he wasn’t shy to ask his subordinates if they had a steady relationship: “If you don’t, I can introduce you to someone.” He liked to control people’s personal relationships and I think that is one of the main characteristics of an abuser. In many cases, I saw young unmarried subordinates who were already very isolated from their circle, because Harvey found them partners from among their own to keep them loyal to Harvey.

Our parents’ generation grew up with this burden of keeping your head down, working hard, not making a fuss, you’re lucky to be here…

But coming back to your Asian roots…

It’s actually a really tricky topic to talk about, because whilst there are behavioral characteristics common to a culture, you also don’t want to overemphasize that, because then you’re racializing it. To say that I act a certain way because I’m Asian – I think that’s a difficult path to walk, and we all need to be careful when playing with racial stereotypes. But still I want to talk about it, because it’s a really nuanced point. I think the racial elements in my sexual assault actually played in pretty early. My New York Times op-ed is entitled: „Harvey Weinstein told me he liked Chinese girls”. During the night of the assault, he would say to me things like, “I like Chinese girls, because they’re discreet, I know you’re not going to talk about anything”. He definitely racialized me by typifying me as a submissive, quiet, compliant person who wasn’t going to make a fuss. When he started saying things like this to me, I just thought, well, if you’re an assistant of somebody famous, like Harvey Weinstein, it’s really important not to tell journalists like where he’s staying in the hotel, or not to reveal his private habits to newspaper articles. I didn’t think it was the context of sexual assault. It wasn’t until later that I realized that his hints about my origin were actually about me not talking because I’m quiet and humble.

I grew up in both an Asian family and the church has also played an important role in my upbringing as the Chinese Church in London was my extended family. I did have a feeling during my childhood, that many subjects were taboo – and not just sexual assault but emotions in general. I think this is true of Asian cultures in Asia, but it’s even more amplified in the diaspora. By that I mean immigrant Asian cultures. Many of my Chinese friends born in America or England share a common experience of their parents: people who have moved to another country, who don’t speak the language, who are poor, and who are trying to establish themselves in a society and culture that they are not a part of. Thus, I think our parents’ generation grew up with this burden of keeping your head down, working hard, not making a fuss, you’re lucky to be here… And if you make a fuss, you might get carted off to Japanese internment camps (during World War II, local Japanese in the USA and Canada were interned in camps. – edit. ). That trauma is very deep in the history of Asian people. Because people still remember that, our parents’ generation has tried to plant in us the attitude that don’t do stupid things, go to a good university, get a good job, become a doctor or a lawyer and be a good member of society. I have seen my parents several times in a situation where they have been pushed to the bottom of the pile in terms of customer service, but they don’t stand up for themselves because they don’t speak English and they don’t want to make a big fuss about it.

It’s a culture where we don’t talk about our deepest feelings, but we blame ourselves, internalize our own guilt, and that’s very dangerous.

I couldn’t stand up for myself as a child either. I was definitely not a person who came forward, who put their own agenda first, who advocated for themselves. My own children, who are grown and live in California, really advocate for themselves. And even though I now speak about assertiveness, I do lots of international talks, and give a lot of interviews, when I was 24 I was very shy. It was my inner attitude, I felt that neither me nor my feelings mattered. It also affected how I got along with Harvey – I just wanted to do a good job and be a really good assistant. But it also affected my personal relationships. When I attempted suicide after Harvey, I had already been in seven-year relationship. Our relationship collapsed because it was all too much for my partner. I blamed myself a lot — partly for Weinstein’s abuse, but also for not being a better girlfriend. I think this cycle of self-blame is a very Asian thing. It’s hard for me to say because I feel like I’m reproducing racial stereotypes. But it is true that in our culture people do not talk about difficult and emotional topics. It’s a culture where we don’t talk about our deepest feelings, but we blame ourselves, internalize our own guilt, and that’s very dangerous.

Rowena Chiu. Foto: Kathy LaBarre

On October 5, 2017, New York Times journalists Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey published an article about Weinstein and his sexual crimes. Cases of extreme sexual harassment had been published also before October 2017, but never got so much attention. Why do you think the case of Harvey Weinstein triggered such a reaction and also the Me Too movement all around the world?

I think one reason is that he was a Hollywood film producer. In some ways, he embodied a woman’s worst nightmare, on the other hand stereotypical, sort of cinematic situations – the man is older, not very good-looking and large; and the woman is beautiful, slim, blonde – like a sort of princess that needs rescuing. By the way, most of the people he singled out for abuse are blondes. So I think there was visually that sort of filmic notion and the media is looking for this visual anti-fairy tale. Also, the world in general is fascinated by Hollywood.

So I think the context played a role – Trump was in the White House and women got fed up. Women had been fighting for decades, generations, and it all reached a social tipping point.

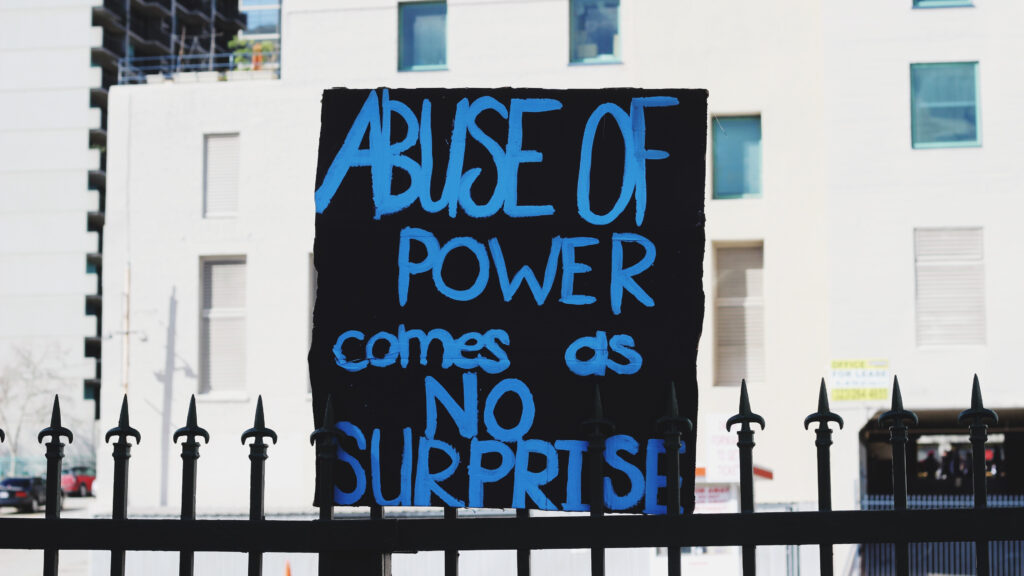

Another important aspect is a cultural context: left-wing liberal coastal elite women who mainly supported Hillary Clinton were extremely angry that in the US, a woman could not get in the White House. Not only were they angry about the fact that Clinton had not won, but they were also especially angry that she’d lost the position to somebody like Donald Trump. The aggrievement went very deep, because Hillary stood for a strong feminist figure, and she lost to someone who was the utter opposite of that. And when a person got into power who was going around talking about getting to grab women’s pussies and kissing them because he’s famous and can do whatever he wants, women who suffered sexual abuse came forward for the first time because the whole situation had gone beyond any limit. Despite everything, Trump got into the White House. So I think women channeled their anger into other areas to try to hold men accountable. It’s very complicated because, as Harvey’s lawyer pointed out: if Brett Kavanaugh and Donald Trump, accused of abuse, could continue their jobs, why shouldn’t Harvey Weinstein, a left-wing Democrat supporter, be able to continue as the chairman of Miramax. This is exactly the argument Weinstein’s lawyer came up with, and it is, of course, quite absurd. So I think the context played a role – Trump was in the White House and women got fed up. Women had been fighting for decades, generations, and it all reached a social tipping point. Women came to the streets, changed laws, wrote and signed petitions because they were simply fed up.

Rowena Chiu. Foto: Kathy LaBarre

After the MeToo movement, many counter-movements or contra movements, like anti-gender, incels, Andrew Tates, have arisen. Do you feel that those movements have canceled some of the efforts made by MeToo?

And also the Amber Heard case. I think if there is a large cultural and social movement, then there would be something wrong if there weren’t any counter-movements, because, in some way counter-movements are an indication that you’re successful and that people are threatened. And there are certainly groups of people who are deeply threatened – misogynists are threatened, incels are threatened. So there are people who feel they have to come out against the MeToo movement because the MeToo movement in many ways speaks against their way of life.

But if we don’t talk about these things, if I don’t directly say this is what is being said to me almost daily, it’s a form of abuse, too.

In the wake of Black Lives Matter and Stop Asian Hate, there was this whole concept of white fragility in the sense that people started saying “but all lives matter.” In some way, All Lives Matter was a contra-movement to Black Lives Matter. And although it didn’t take off in the same way, there was indeed a core group of people who were very vocal and who said, why should we give a platform to black lives, what about everybody? And that sounds virtuous until you begin to pick it apart and you understand that, well, what you’re really saying is that you want to maintain the status quo where black people are very oppressed in this country. It’s the same with the counter-movements for the MeToo movement: they will use an argument that seems very sensible and logical. But, when you begin to pick it apart, what they’re saying is: we don’t acknowledge the fact that women have been oppressed at all.

While we’re on the subject of incels, I want to also mention ricecels. Traditionally ricecels has been used as a word to depict sort of geeky Asian men who can’t get a girlfriend. But there’s another definition of this word – white guys thinking that Asian women are compliant, submissive, docile, and often economically in poverty. Those men might be wealthy people who’ve graduated from great universities and work for a multinational company somewhere in Asia. They pick a girlfriend who might come from a rural area, one of the less high-income Asian countries (Philippines, Vietnam, etc), because they know their economic power will mean that person will never walk away from them. And they could be someone who didn’t get a girlfriend back in London. We have this horrible acronym in Hong Kong called FILTH – failed in London, try Hong Kong. But in Asia, there are mid-level white guys, who are really feeling that their economic power or their racial power and privilege really come into play. And they don’t want to go back to wherever they came from. Interracial power relations are a complex issue that depend largely on the context.

There is no single point in time or situation where it dawns on others that the person is an abuser. That realization is gradual.

I have had a dark peek into the issue concerning ricels. Because I’m a public figure and there are now lots of photos of me on the internet, I get correspondence from the counter-movement at least a few times a week. They’re generally unpleasant, along the lines of “Oh, you cute Asian girl, you know, I’m feeling horny, get to bed with me”, or even worse than that. But there is also a counter-movement with such a mentality, where men are expectant of sex and they are against women who are too outspoken. The main message of that movement is “instead of getting up and talking so much, you must be sexually frustrated, come over here, and I will show you a good time. And then you won’t want to talk about it.” And it is filthy and disgusting. But if we don’t talk about these things, if I don’t directly say this is what is being said to me almost daily, it’s a form of abuse, too. Let’s not keep these things silent because if we as women don’t say them in interviews and we don’t shine a light on it, we’re doing ourselves a disservice.

Peakpx, CC0

When it comes to bullying at school, they say there are three parts: the bully, the victim and then there are bystanders, who are just observing, but they don’t do anything about it. Because of the bystanders, this can happen. If there wouldn’t be those bystanders, then actually, the bully wouldn’t have an audience, and it could not go on. What do you think, how could we encourage more people to be like Zelda Perkins and stand up for evilness?

My context was that I lost my job, I was stalked by a spy, Harvey accomplished that my whole life fell apart. Another important point is that sexual assault is not like how it’s portrayed in the movies. There’s not a moment in time when the assailant jumps on you, and then you decide to scream and run. It’s often you’re in a room, and they’re putting subtle, coercive power on you. And this might happen, as it did in my case, over hours, maybe even days, weeks, or even years. A deeper understanding of how sexual assault works, as in it’s a power imbalance, and somebody is kind of coercing you to do something, is really important. That’s also true for the bystanders. There isn’t a moment when Harvey jumped on someone in a hotel lobby and raped them on the floor, so you couldn’t say to yourself, “Oh my god, I’m working for a rapist”. There is no single point in time or situation where it dawns on others that the person is an abuser. That realization is gradual.

There’s an uncomfortable feeling that maybe all the girls you’re taking to the room aren’t very happy to be there. Normally, it’s just everyday business, which of course, wasn’t pleasant in Harvey’s office. But there wasn’t like a defining moment where you went, okay, I’m going to be an upstander because this event has happened, and I cannot let it. Of course, Zelda did have that defining moment, but even for her I was the last in a long line of assistance that she had tried to hire for Harvey. And I think, I essentially was the straw that broke the camel’s back. It’s hard for a bystander to find a defining moment because you’ve been lulled into understanding that this kind of behavior is normal.

But I also think that the MeToo movement hopefully changed society at least minimally and now it is possible to talk more about sexual abuse. The fact that there are these kinds of conversations encourages me, because every single one of these conversations is empowering. The fact that there are millions of other women around the world that are now empowered to speak out about these issues does make the individual person feel like they are no longer alone with their problems.