Have you ever heard of „Gayropa“?

Kevin Snow, a former Fulbright scholar in political science who worked as a researcher in Estonia, analyzes the geographical identity of Eastern Europe, more specifically, the role of rhetoric based on geographical identity in discussions of the rights of LGBT+ people. Considering that Estonia is located on the border of Europe where there is a war going on, this issue is particularly important.

Maybe you haven’t heard it but have read it in a comment section online. If you did read it, you probably assumed it was the juvenile humor of a bigot – just someone online who believes it is the height of comedy to combine „Europe“ and „Gay“. Your instinct makes sense. Certainly, no serious person could possibly speak about „Gayropa“ without blushing in embarrassment.

Unfortunately, this phrase has a great deal of importance within the Russian government’s worldview. To Putin and his cronies, it encapsulates their disdain for the tolerance and acceptance of LGBT+ people within Europe, as well as the United States and other Western-aligned states. The phrase began to gain wider traction during the early stages of Ukraine’s deliberation over closer integration with the European Union. „Gayropa“ was a part of the wider rhetoric used by Russian state media to stoke fears of LGBT+ people, which also included claims that in Brussels children are sold at fairs to gay men, or that pride parades in EU-aspirant states like Ukraine and Georgia are state-organized to appear western. In Russian media and political narratives, the West’s decline is tied to the decline of masculine authority and the acceptance of „deviant lifestyles“. This rhetoric has not disappeared and has been used during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

With the current Russian invasion of Ukraine and a recent spate of articles in the Anglophone press on the war’s implication for LGBT+ people, it is important to consider the role of geographic rhetoric in debates on LGBT+ rights. Given Estonia’s place as Europe’s frontier, it’s a conversation that is important to have here.

What is the Nation to an LGBT+ Person?

First, we need to consider what a nation is and what geography means to a nation. A nation is, in essence, a group organized around shared characteristics of language, ethnicity, race, religion, location, traditions, values, etc. The exact combination of characteristics is not essential to the legitimacy of a nation. Instead, how these characteristics are woven into a unified identity among a group of people is what is essential (Anderson, 2006). The creation of a national identity is one based on the creation of a shared history and purpose resulting in what Benedict Anderson refers to as „imagined communities“. This is done to create a group identity. Just like all group identities, national identities rely on this to create in-groups and out-groups. If all people are a part of a group, then there is no out-group to provide an example to differentiate difference from the in-group.

This doesn’t mean that there is a consistent measurement for what makes someone part of a nation. There is a never-ending process of defining and redefining what it means to be „us“ instead of „them“ (Lamont & Molnár, 2002, pp. 169–171).

Boundaries are an important concept here – what divides the in-groups and out-groups from one another. Some boundaries can be set that are more inclusive or exclusive, e.g., „valuing democracy“ is more inclusive whereas „speaking the language“ is more exclusive. An essential and largely exclusive boundary is that of location. If someone is born in a specific location, they have a greater claim to whatever national identity is prevalent in that location. It is not the only source of legitimacy, but one that is often used rhetorically; for instance, arguing that someone is less Estonian because they moved to another country.

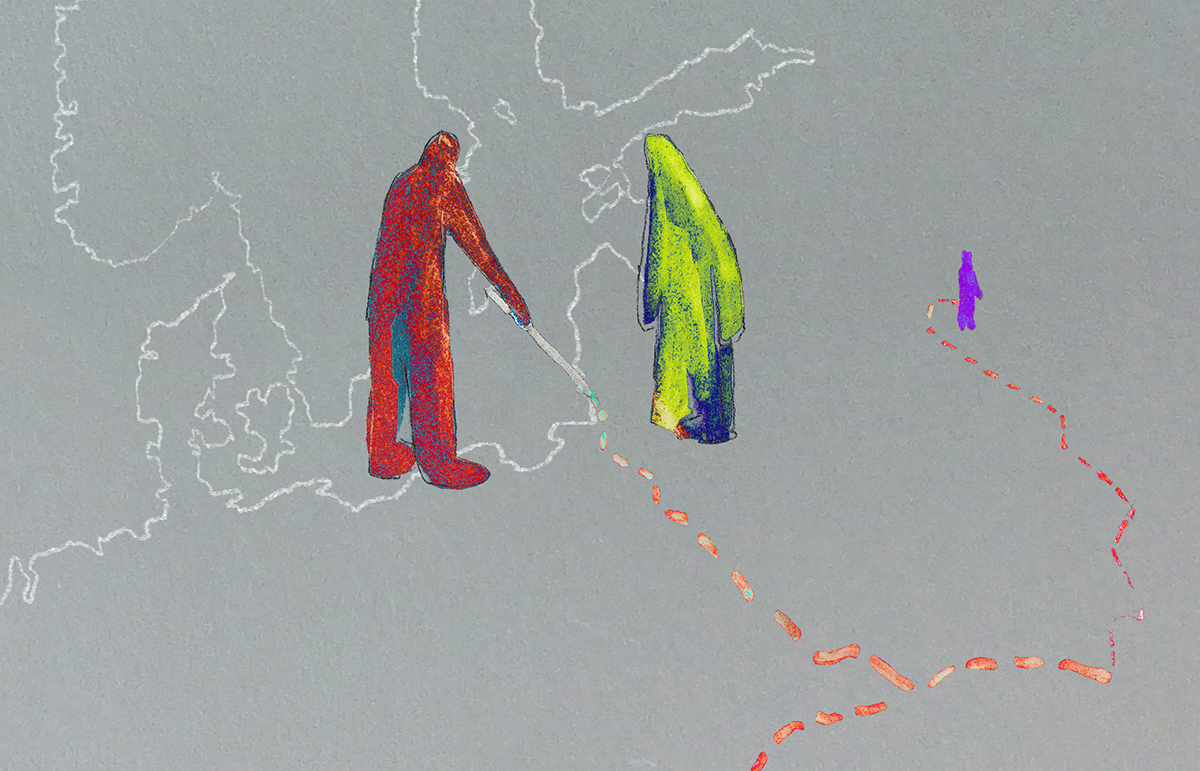

Illustration by Rodion Furs

Marking as a Foreign Other has Been Effective

Why does any of this matter for LGBT+ rights? It matters largely because LGBT+ people have existed through all times, in all places, and in all societies. Despite this, anti-LGBT+ rhetoric often seeks to situate LGBT+ identities as an import from outside the society. This is why opponents of gender and sexual diversity in different societies target LGBT+ identifying people as representing a threat from a foreign other (Underwood, 2011).

Universal categories of identity (meaning identities that transcend barriers like language, region, ethnicity, race etc.) do not make for easy distinctions between us and them. These universal categories are a part of arguments over values, traditions, preservation of the nation, etc. Embracing LGBT+ rights represents a toleration of difference that is unacceptable to nationalists. So those same forces tie LGBT+ identities to foreign influence. We have already briefly looked at Russian rhetoric on LGBT+ people, but there are plenty of examples closer to home. Mart Helme, former leader of EKRE and former Interior Minister infamously said that gay people should simply „run away to Sweden“.

Using geography to reinforce the supposed foreignness of LGBT+ people has been effective. It has worked well in Russia, China, as well as countries like Uganda and Iraq. Does that mean that geographic rhetoric is crippling for LGBT+ rights? That would be the right conclusion depending on an important variable. The society that you are within needs to have an established hostility or weariness towards the foreign „them“ that you are addressing. Hostility towards LGBT+ identifying people within Russia has often been filtered through an existing disdain for „the West“. The beginning of LGBT+ activism within Russia started to slowly emerge in the late-Soviet era. This initial stage of activism was, in part, inspired by the civic activism that defined the fight for gay rights in the West during the 60’s and 70’s. Pride parades, „coming out“ LGBT+ organizing, these are seen, at best, as a „western way of doing things“. At the worst, it is seen as a deliberate attempt to subvert Russian culture through „gay propaganda“ (Verpoest, 2017).

Illustration by Rodion Furs

Is all Geographic Rhetoric Hostile to LGBT+ People?

While geographic rhetoric is a tool that works for anti-LGBT+ efforts, it is not one totally unavailable to pro-LGBT+ efforts as well. Estonia is an excellent example of this framing working in reverse. For Estonians, integration into „the West“ was the driving priority of much of the first two decades of independence. Estonia not only sought to join the formal institutions of the European Union and NATO but to be recognized as culturally tied to the West. Much has been made before about Estonia’s Nordic/Western ties, such as linguistic and ethnic heritage with the Finns, or the role of Sweden and the Baltic Germans in the country’s history (Lagerspetz, 2003, pp. 52–55). This identification has often been helped along by a desire to no longer be affiliated with Russia (Drechsler, 1995).

This is observable in the use of geographic rhetoric in the debates around the Civil Partnership Act in 2014. During the debates on the Civil Partnership Act in Estonia, LGBT+ activists and their allies used geographic locations to their advantage. Being in opposition to LGBT+ rights was framed as remaining within a Soviet mindset, or of being within Russia’s sphere. One opinion piece in ERR by the author Sirje Kiin illustrates this framing well: „Opposition to Civil Partnership Bill Is a Vestige of Authoritarian, Eastern Mindsets“. In the article, Kiin points to polling data in Estonia that showed a slight majority of Estonians support same-sex cohabitation legislation, whereas only a third of Russians in Estonia do, a difference she believes: „Points to the intolerance prevalent in Russian social space, which has today been inflated to strident anti-gay propaganda that has taken on a form that disparages all Western values.“

Kiin is not alone in this framing. This focus on how international audiences would perceive the legalization of same-sex partnerships was likely a major factor in the passage of legislation that was deeply polarizing at the time. On the law’s passage, many foreign publications did treat it as proof of Estonia as a liberal, western country and others lauded the decision as a rebuke of Russian/Soviet influence.

International media covered the passage largely through the lens of Estonia as a trend-setter for other post-Soviet states. It was an example of where the region may go after embracing the liberal, multicultural example of the Western EU member states. On a less positive note, this international coverage failed to mention that the legalization of partnerships was never fully implemented and continues to present challenges for same-sex couples. A more pessimistic reading of the Civil Partnership Act is that its passage was just an attempt to appear like more of a member of the club of advanced democracies, without truly embracing the actual values involved. How genuine was the embrace of the „western“ value of LGBT+ rights? Did that embrace mean anything to LGBT+ people, given its shortcomings?

So Why Does that Matter Now?

Puzzled by these questions, I came to Estonia as a Fulbright scholar in 2021 to talk to Estonian LGBT+ activists about what Estonian, Nordic, European, Eastern, and other such identities meant to them. I had the chance to talk to activists and was surprised how few people really cared about being Nordic. More generally, people considered themselves European, „Eastern with Nordic nuances“, or rejected the idea of national identity altogether. The rhetoric of Europe and the Nordics was considered a useful tool in the context of rights promotion in Estonia, but its actual place within their own identities was not apparent. Those interviews I conducted largely concluded before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24th. If I did those interviews now, I wonder how LGBT+ activists would make sense of those identities. There is a concept in political science and international relations known as the „rally ‘round the flag“ effect. In times of external crisis, people not only become more likely to support their government and political leaders but also to rally in support of their country in general. I have had conversations and seen plenty of social media posts that point to a hardening of views around Russian culture and society.

Now, the war in Ukraine is being framed not only as a civilizational struggle in Russia but also in Western media. Does this rhetoric represent a chance for the advancement of LGBT+ rights in Estonia and Eastern Europe more broadly? So far, there’s some signs that it’s being used that way. In Romania, one major LGBT+ group has framed new anti-LGBT+ legislation as „fuel“ to „Russian propaganda and Moscow disinformation campaigns“.

Talking to activists, they often felt that Estonia is slowly moving positively on LGBT+ issues. Perhaps the adoption of this language again is worth considering. It has been used to good effect before and offers solidarity with other European LGBT+ organizations. It is also a way to speak the language of the wider Estonian public, which despite the rise of EKRE, remains more pro-Europe than the publics of most states in the EU.

For myself, I am cautious about the adoption of the language of nations and geography. If we accept the idea that LGBT+ rights are Western, we run the risk of abandoning the universal aspect of LGBT+ identities. Treating LGBT+ rights as a part of Western culture may very well validate attempts to tie the rights of LGBT+ people with foreign subversion. That is the risk present in embracing geographic rhetoric. That does not mean it is without merit. I do not seek to judge the decisions of activists or Estonians generally. The trauma of Estonia’s past and the continued threat that Russia presents makes geographic narratives far more significant for Estonians than for me as an American. It is imperative to question if geographic rhetoric is in the best interest of LGBT+ people in Estonia. If we talk about LGBT+ rights as a „Western value“, does that help validate those who tell LGBT+ people around the world that they belong in Gayropa?

References

Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. 2nd ed. Verso.

Drechsler, W. (1995). Estonia in Transition. World Affairs, 157(3), 111–117.

Khor, Diana, et al. (2020). Global Norms, State Regulations, and Local Activism: Marriage Equality and Same-Sex Partnership, Sexual Orientation, and Gender Identity Rights in Japan and Hong Kong. Oxford Handbook of LGBT and Sexual Diversity Activism.

Lagerspetz, M. (2003). How Many Nordic Countries? Possibilities and Limits of Geopolitical Identity Construction. Cooperation and Conflict, 38(1), 49–61.

Lamont, M., & Molnár, V. (2002). The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 167–195.

Underwood, A. E. M. (2011). The Politics of Pride: The LGBT Movement and Post-Soviet Democracy. Harvard International Review, 33(1), 42–46.

Verpoest, L. (2017). The End of Rhetorics: LGBT policies in Russia and the European Union. Studia Diplomatica, 68(4), 3–20.