Uzma Yakoob: Pakistani feminism is secular, diverse and inclusive

What are the feminist narratives in Pakistan? How are women affected by militarism, patriarchy, unstable neighbouring countries, Islam and colonial legacies? What was the impact of the Soviet war in Afghanistan on women’s rights, and how are the rights of gender and sexual minorities guaranteed in Pakistan? In May 2022, Hille Hanso interviewed Uzma Yakoob, a human rights activist with 10 years of experience. It’s a long and interesting story, enjoy!

Uzma Yakoob is committed to supporting marginalised and socially excluded women and trans people, in all their diversity. She is the founder and Executive Director of the Forum for Dignity Initiatives – FDI. The Forum for Dignity is a research and advocacy forum on civil and political rights, civic participation and leadership; sexual and reproductive health; and advocacy for women’s and trans rights. Uzma is committed to challenging social taboos and working to make Pakistani society a better place for socially excluded and marginalised groups.

Pakistan is currently in the news everywhere due to political instability. Could you briefly summarise the nature of the current political problems in Pakistan?

It is Pakistan’s misfortune since independence that there has never been true democracy and power is in the hands of the military. None of the elected prime ministers of Pakistan, ever completed their term of office, they have either been removed by a vote of no confidence or military rule has been imposed and the government has been dissolved. Similarly, the Pakistan Tehreek Insaf (PTI), led by Imran Khan, faced a no-confidence vote this time too, backed by the military. There is distrust between political parties and, similarly, the population does not trust the parties and their leaderships. However, the military institution is feared to be criticised or provoked.

Pakistan is not a well-known place for Estonians. How would you describe Pakistan’s society and political structure in general?

Pakistan is a democratic republic, but also an Islamic country. We call it an Islamic democracy, but we have had almost 40 years of martial law or military dictatorship out of our 74 years of independence. When we accuse Pakistan’s politicians of inaptitude, we must not forget that they have never been given enough room for their true political representation and parliamentary business. The important decisions are in the hands of the military: justifications by the military are technical or point to Pakistan’s borders with India, Iran, China and Afghanistan. It was not possible to avoid either the Soviet-instigated war in Afghanistan or the US-led shadow war against the Soviet Union. A long border with India means constant conflict over Kashmir. Huge sums are being put into the defence budget. So there is very little left over for politicians to invest on human development.

Women in Pakistani military. Photo: Heiki Meos

How much of the national budget goes to the military?

Military spending is never made public. It is estimated that between 70–75% goes to the military (a claim often heard in the Pakistani public media as well as in the popular press, HH). In my opinion, the defence budget accounts for almost 60% of the overall budget. Out of the remaining 40%, the government can pay salaries and pensions and take care of infrastructure and individual developments. The critical needs are marked as soft stuff and not prioritized: health, research and development, even education. The education budget is mainly used to pay for overheads, so there is no room for improving the quality of education: commissioning research and development, building good or safe educational facilities, constructing new buildings, setting up libraries or laboratories.

What role does the colonial past play in all this?

Pakistan’s penal code is still based on colonial law. The legal systems of both Pakistan and India are descended from British law. These laws came from a country that was different from India and Pakistan in almost every way – religion, culture, society, economy, even language. The British laws of 1935 continue to shape our daily lives and our law today. To give a very simple example, Section 377 of the Pakistan Penal Code criminalises homosexuality. This is not part of the culture, society or customs here, and the welfare state was at the heart of the creation of the republic. It is thought that Pakistan has never had the finances to review all the laws and create a new legal system. What we need now is laws that are more beneficial to all members of society irrespective of religion, culture and caste.

How do the above-mentioned factors together – militarism, unstable and patriarchal neighbourhoods, Islam and colonial heritage – affect women in society?

I believe that women are among the most vulnerable groups. As there is not much money in the national budget for education, the male population is at an advantage. Girls tend to miss school because of menstruation. If they have to walk 2 to 3 km to school, they may not go because it is harder for them to walk to school every day, their physical safety is not guaranteed and they are sexually harassed; extreme weather conditions are also a barrier. Many of the girls cannot afford private transport or to pay for rickshaws and schools do not provide transport. Menstruation is a particular problem for girls, as schools either do not have toilets at all or, if they do, they are not in working order, with no sanitary facilities, running water, locks on doors or lighting. Many women suffer from malnutrition because they never have enough or good food – milk and other protein foods are more likely to be given to men because they have to look after the family, go out to work, and so on.

Many families have six or seven children (in Pakistan, there were 3.45 children born per woman in 2019, while fertility per woman is on a downward trend. – HH). Women’s reproductive burden is compounded by miscarriages and abortions. The pay gap should not be forgotten. Women work in factories as packers, for example. If women are embroiderers or do other handicrafts, it is definitely the man who is the distributor, as he has easier access to markets. In many (rural) areas, it is not customary for women to go out of the home or earn money. The share of women in the formal labour market is around 25%. One thing is the general lack of a transport network. Another is traditional values and culture. In many places, people do not like to deal with the government and go to work. For example, in Pakistan women work at home and in the field, factories to make money for the family. The saddest thing is that women’s work is not formally recognised, which means that labour laws do not protect women and their earnings are not included in GDP, even though they pay indirect taxes in one way or another.

You have said that before 1979 Pakistan was more liberal. What happened that year?

The founder of the Pakistani state is Mohammed Ali Jinnah, who graduated from Oxford University and worked as a lawyer, led the independence movement that led to the creation of the State of Pakistan on 14th of August 1947. He and his comrades-in-arms set their sights on an Islamic country that would be progressive. Jinnah insisted on 11th of August 1947 that the state he was building was not a religious state. We have the opportunity to visit mosques, temples or other shrines and enjoy the joy of living in a progressive country. It is the duty of the state to protect our rights and this speech gave Pakistan a face. But in 1979, Afghanistan was invaded by the Soviet Union. Since it was the right moment to break the bipolar world system and break up the Soviet Union, the US naturally wanted to confront it.

At the time we were ruled by General Zia ul-Haq, who decided to go to Afghanistan under the banner of Islam. The firebrands even started talking about invading the Soviet Union. Why Pakistan went along with it, I do not know. Our country was deprived of its honour, but all it got in return was a handful of dollars. Drugs and weapons flooded in. Although there were exceptions, of course, in the past our young people did not care about drugs. With the borders now open, young people could become mujahideen. Since the Kashmir front had existed before, we were now holding two military fronts in the name of Islam. That was the turning point for Pakistan – the weakening of progressive Islamic state. If General Zia ul-Haq had not seized power of political and elected government and plunged Pakistan into a pitch war, we would now be one of the advanced countries, because we had been making rapid progress. (Although Pakistan became independent in 1947, the first constitution was ratified in 1973. In order for it to be adopted, a number of concessions had to be made to influential conservative Islamists. The constitution declares that all existing laws shall be brought into conformity with Islamic injunctions as laid down in the Qur’an and Sunnah, and no law shall be passed which is inconsistent with such injunctions. – HH).

Uzma Yakoob, a human rights activist who holds two master’s degrees, is an influencer, public speaker and blogger. On the photo with the FDI team and the trans community. Photo: FDI

Was it easier to mobilise people in the name of faith? Were there setbacks?

In the name of Islam, life began to change. Religious leaders introduced a new regime: women were no longer allowed to go out. If a woman was found guilty of adultery, she was given 70 lashes and then publicly stoned to death. On the other hand, because laws were passed to restrict women’s rights, the women’s movement in Pakistan was only really beginning.

I was going to ask whether this did not provoke a reaction from women?

It did. Then a women’s forum was set up. The world-famous Mrs Nigar died a few years ago (Mohtarma Nigar Ahmed (1945–2017) was a Pakistani women’s rights activist who founded the Women’s Action Forum and the Aurat Foundation, which is still active in promoting women’s rights today, HH). We are sincerely grateful to the 10 to 15 women with resilience who defied the military regime.

Since you said that militarism and conservatism were opposed by the feminist movement, what are the narratives of Pakistani feminists? Pacifism? Human rights based on Islamic principles? Something else?

Pakistani feminists do not form a coherent movement. Feminists include both religious and secular people and therefore do not base their demands on religious values, their approach is inclusive. If there is one goal, it is that women should be able to do everything that men are entitled to do. The constitution explicitly prohibits gender discrimination. Unlike certain European countries or US states, women’s right to vote was already enshrined in Pakistan’s first constitution. We were the first Islamic country to have a female Prime Minister. Our Speaker of the National Assembly was Fahmida Mirza. Women are restricted not by the constitution, but by the way it is enforced, and unfortunately the military authorities have always promoted a right-wing agenda, with the exception of the Musharraf regime in 2008–2013. Although he was a general who became president of the country by referendum, his government was progressive. He did a lot for women’s rights. Unfortunately, because Musharraf was a general, he is seen in dark shades. It would have been more praiseworthy if women’s rights or media freedom had been implemented by a government of politicians.

What does right-wing mean in the Pakistani context?

Religious extremism. Nationalism has always existed in the military establishment. This is how the military budget is justified. Right-wing extremism means strengthening religious extremism. Religious extremism, in turn, means power over women’s bodies, freedom of movement and rights.

Islamists have many ways of interpreting this religion as egalitarian. How widespread is Islamic feminism in Pakistan?

We don’t have Islamic feminism. Feminists in Pakistan are not looking for sympathy from their religious leaders. One of the few principles we agree on is that Pakistani feminism is secular, diverse and inclusive. These are principles we put into practice. Of course, there are tensions between different groups, but mostly it is about recognition, funding or access to resources. The ideological differences are, I think, a result of the differences of the individuals. We women are at different points in our feminist journey: those who consider us to be fully equal to men, those who do not.

We do not want less space for men, but we are asking for our space not to be reduced. In my opinion, there is no need to take a separate planet for each gender. This single planet must be shared fruitfully, sensibly and respectfully. Certain groups think that men are not needed, but I do not. I love my father and my brothers and am happy with my male friends and colleagues.

FDI core team. Photo: FDI

What are the most important laws that the feminist movement in Pakistan has fought for?

Sad to admit, but all these laws came under the rule of General Musharraf, who was a fierce advocate of women’s rights. We had the Protection of Women Act. The law against harassment in the workplace came. We had the Child Protection Act. We got a law to protect women’s property rights. A law against honour killings was essential because women were being killed in the name of honour. All these ground-breaking laws were passed in 2008–2011.

Several scandalous honour killings have come to the world’s attention, and books have been written about Qandeel Balouch. Has the law managed to stifle this practice?

The law has been of some help, although there are fundamental flaws in the requirements for witnesses and evidence. Usually, someone offers a bribe before a trial to get evidence removed or destroyed so that people will not testify in court. Of course, the court will do its best to ensure that the decision is not based on media coverage or public opinion, but on the evidence and the law.

What should one think about the legal provision that the victim’s family can forgive the offender?

It is now forbidden by law for relatives to give up the blame. Murders almost always take place between members of the same family. There are 220 million of us and the courts are overwhelmed. One court has thousands of cases pending. Sometimes a defendant dies without waiting for a decision. (Also, honour killings are now being committed in a more devious way, e.g. by forcing women or girls to kill themselves, e.g. by jumping off mountains, drowning or poisoning themselves. The killing is then recorded as suicide. HH)

How would you describe the situation of LGBTQ+ rights in Pakistan?

Same-sex relationships are not recognised in Pakistan, only gender minorities. You can get a surgeon to do gender correction surgery if you want. Pakistan recognises intersex and transgender people, but not lesbians, gays, bisexuals or quasi-sexuals. For transgender people, Pakistan passed the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, 2018 in March 2018, with the most important right to self-determination of gender identity. Compared to the rest of South Asia, even certain European countries or US states, the law is very comprehensive: it talks about the right to inherit, the right to education, the right to run for and hold elected office, the right to vote, the right to economic empowerment. Unfortunately, the law is silent on the right of trans people to form a family, their chosen or biological family, the right to have children, to have a spouse or partner. However, as representatives of the trans community, we are satisfied that at least something is in place to protect trans people from violence or depriving them of their rights.

Trans women face common gender discrimination though – they are not visible in Pakistan because of deeply entrenched patriarchal norms. They face the same restrictions in society as other biological women.

Female to male transition is not only accepted, it is cheered on the basis of gender preferences because there will be more men in the family. However, if trans men assert their sexual rights and choose a biological woman as their intimate partner or spouse, the same family may demand that she be punished by calling her homosexual. So, there are contradictions.

Trans community gathering in Islamabad, Pakistan. Photo: Hille Hanso

The transition from maleto female, is it Shariah-compliant?

In Sharia it is very clear. It also applies to trans people. If you identify yourself as a woman, you inherit the woman’s portion. If you identify as a man, you inherit a man’s portion. If families decide to divide the inheritance equally, this is also not forbidden. In any case, the Sharia lays down a minimum principle. A man inherits only from his parents, but a woman also inherits from her husband.

Note that FDI is currently deeply concerned with ongoing propaganda to undo the “Transgender Persons Protection of Rights Act 2018 in Pakistan”. There are number of social media campaigns going on against the law, the dignity and right of self-perceived identity of transgender persons in Pakistan. FDI urges the state to take assertive actions to protect this law and lives of the people involved in risk through this ongoing propaganda.

Even though the society is more or less progressive, the trans community faces many challenges. What are they in Pakistan?

Although trans people are equal before the law, sometimes this does not help to break stereotypes or social norms. Pakistan’s constitution, which came into force in 1973, has at least 28 paragraphs that talk about ensuring human rights. We have got the Transgender Protection Act as a supplement. Even before this law was passed, the police had no powers to ill-treat trans people for expressing their gender identity. Schools, hospitals, etc. had no power to refuse admission. In Pakistani society, trans people are accepted and respected until they are seen as marginalised, begging. But when trans people want equal rights and recognition as citizens, a problem arises because the system and the people see it as an egoistic desire.

Social norms, stereotypes are an obstacle. However, I think that the law makes things better. The trans community in Pakistan is very lucky because they get a lot of attention. You see trans people all the time on our social media and on national channels, even during the most watched hours. On the Pakistani minority spectrum, this is something unusual. Five transgender candidates contested the 2018 elections in Pakistan. Of course they didn’t win, but it was still a step forward. What I always say about stereotypes is that we shouldn’t be offended at people because they are learning how to respond to diversity in an inclusive way. When we come back to the same issue in 10 or 15 years’ time, the perspectives and experiences may be completely different.

Unlike the trans community, religious and ethnic minorities have specific political baggage attached to them and this creates divisions.

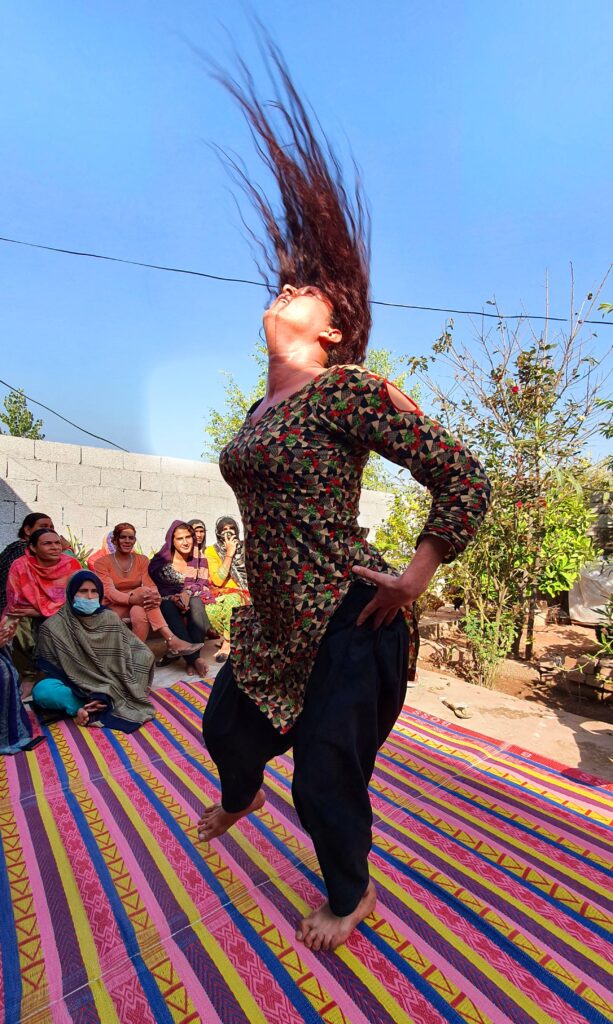

Dancing, sex work and begging are the main sources of income for the transgender community. Photo: Hille Hanso

Does it contribute to the acceptance of other minorities, such as gays?

Unfortunately not, I don’t think that in Pakistan in the next 50 years lesbians, gays or bisexuals will be recognised. In essence, homosexuality is seen as an unnatural manifestation of intimacy or sexual relations.

Personally, I think people need to understand that sexual orientation is something private. People should not peep into other people’s trousers or beds. However, in an Islamic Republic, this remains a problem, because homosexuality is forbidden in Islam. I don’t know whether strictly or it is a matter of interpretation. Perhaps new generations will invest in research and convince people of the need for recognition.

Would you like to say a few words about diversity? Sufi thinking in Islam is completely different from Wahhabism or other fundamentalist trends and advocates pluralism. Which schools of thought prevail?

Sufism is one of the most progressive expressions of Islam as a religion because it is more accepting, more diverse, more inclusive, more peaceful. There is a widespread perception that Sufis do not adhere to Sharia, although this is not true. Unfortunately, Sufism does not have the potential to gain wider support in society because of the militarisation of democracy. Former Prime Minister Imran Khan was a practising Muslim who exhorted people to convert. He went to various shrines with his wife. He did not want to incorporate Sufi values into curricula or policymaking. (The current Prime Minister, Shehbaz Sharif, is also a religious conservative – he is president of the Sunni and conservative Muslim League of Pakistan (Nawaz). HH)

How are Pakistan’s women politicians doing? What are the parties doing to engage women?

Frankly, the parties are not interested in women’s participation. They are constitutionally obliged to include women, as there is a 33% quota for women. Parties are constantly advised to give women seats in constituencies they can count on. Electoral reform in Pakistan in 2017 mandated all parties to give 5% of the seats on the list in each constituency to women. Otherwise, the election results would be declared invalid. Nobody cared. The Election Commission imposed penalties for non-compliance, but they were of no help. In parliament, women make up at least 17%, but in government, women did not get important ministerial portfolios, either for defence, health or education. There is a female climate minister and a couple of other ministers. Even if women were to get important ministerial posts, I am not sure they would be allowed to make important decisions on women’s rights in health, education or employment.

In some constituencies women are not voting due to a number of reasons, for example, they don’t have identity documents. At the same time, the election results are not valid because the women did not turn up.

Yes, Pakistan’s 2017 electoral reform requires that if the turnout of women in a constituency is not at least 20%, the elections are repeated. This is very good. In the last elections, this happened in a number of constituencies; not a single woman voted and the election in that constituency was null and void. Unfortunately, within the 17%, there are women who are in Parliament simply because they are married to a senator or a member of the National Assembly. For every five seats in Parliament, there is an additional one woman. Now the formula is that five equals one; before it was that three equalled one. If the male members of a woman’s family win seats, they bring her into parliament. She’s not there because she’s interested in politics. That is the sad reality. Half of the women in parliament are the wives of National Assembly deputies and half are the wives of senators. Family business! No woman can be forbidden to enter politics, but women are of little use in Parliament if they have no political motives, if they are there only because they have a husband, mother-in-law or brother-in-law.

Women waiting in line to cast their votes. Photo: EUEOM Pakistan 2013

How do women influence politics in Pakistan?

Parties are most successful when they are persuaded by women behind the voters’ doors. Parties succeed largely because of the efforts of women workers. Readers need to understand that Pakistan is not a conservative society per se. Our wonderful women are everywhere. Pakistani law allows women to express themselves. It is a matter of social norms and, in some cases, political reasons. What counts is who has more contacts. Resources are particularly important in active politics, if only for campaigning – women either do not have enough resources or none at all. There are particularly no economically independent women.

However, little by little, we are seeing changes: Pakistani women and girls are now entering universities. I recently went to college, which I graduated from in my day. I was delighted to see thousands of young women studying there. When I graduated in 2000, only a couple of hundred women graduated. But now, new disciplines and subjects have been added.

In our time, there were only a few disciplines, such as English literature, social work, economics, psychology. Now they study media, natural sciences, international development and development aid, etc, and women are more visible. We are very progressive in many ways.

Yes, there are areas where women are stuck in dark ages practices. Probably the biggest barrier to women’s more active participation is the lack of economic independence. But nowadays women are more visible in public spaces, such as markets or shopping centres. I have noticed that women work miracles wherever they can. I would like to dispel the misconception among readers that Pakistan is an inherently conservative society.

You mentioned that the feminist movements here are mainly based on secular arguments. You work in the Forum for Dignity Initiatives (FDI). How does your organisation achieve its goals and what goals have you set?

The FDI is a research-oriented initiative and pressure group. If we want young women to participate meaningfully in politics both inside and outside parliament, structural changes are needed in political parties so that women’s rights are not only represented in their manifestos but also in their governing bodies. Young women should be given positions of responsibility, such as general secretary or financial secretary, in which they can prepare for parliamentary work. It is necessary to involve women in active politics at local and regional elections, then at national level. This is what the Dignity Forum is trying to achieve for women in Pakistan. Of course, we have both shorter- and longer-term goals.

When we started, there were not many organisations in Pakistan working on minority rights, especially trans rights. There was a tremendous amount of work being done on HIV prevention, treatment and rehabilitation, saving lives. The Dignity Forum wanted to take a broader perspective. We wanted to work on integration, to give marginalised groups better educational opportunities so that they had the choice to pursue themselves in the mainstream economy instead of sex work, begging and dancing. Marginalised groups do not just need to be provided with condoms or lubricants, but the state needs to take care of their health in all aspects. Our aim is to create an inclusive and safe society where all people, in all their diversity, feel safe and fulfil their full potential, whether they want to be educators, activists, researchers, etc.

Many employers want to be more inclusive and hire trans people. Unfortunately, they need to have at least a secondary education. In trans community, they can read and write and use a computer a little, but they lack formal education. Secondly, they may not be able to earn a regular wage because they earn more from begging, dancing or sex work. Unfortunately, no one can be paid 100 000 rupees (almost €500, while the average salary in 2021 was around €459 per month). HH) just because he or she is a trans person, but has to be based on labour market conditions. Wages are a major source of contention, as trans people want to be paid more than their educational background, experience and skills allow.

We are approached by hotels, corporations and banks, asking us to recommend trans candidates who would be the best fit. Unfortunately, we don’t find them easily. Of the hundreds of trans people we know, there are few who would be suitable for staff positions, especially in research or lobbying.

As we believe that much has been done on the legal side, what is needed now is to put inclusion into practice – to provide education and to include trans people in the workforce, to get more transgender students and lecturers.

Can you give examples of success stories?

First of all, the success of the Dignity Forum is proven by the (todays debated, HH) Transgender Persons Protection of Rights Act itself, because since 2013 we were one of the pressure groups that helped the Senate committee on this. Then in 2019, we participated in the development of the Action Plan for the Protection of Transgender People. We were awarded the Human Rights Award by the Government of Pakistan. We received an award from the Global Consortium for Young Women’s Empowerment in recognition of our work on reproductive health, rights and political participation of young women. We are now lobbying for a 2% quota for young parliamentarians aged 18–24. We are also persuading political parties that if there is a fifth of female candidates on the lists, at least 2% should be allocated to young women aged 18 and over.

We have set ourselves clear targets to lobby for. We are proud that all five transgender candidates in the 2018 elections were graduated from the Dignity Forum leadership courses on political participation. We teach the legal and constitutional framework, regional law, international treaties and conventions in our leadership courses. Based on their theoretical knowledge, candidates develop their own action plan and then organise model campaigns. They join mock campaign to practise aspiring as elected representatives. They go out to constituencies to campaign and present their election manifesto to communities.

Votes being counted in the womens’ voting station. Photo: EUEOM Pakistan 2013

Does the ‘West’ sufficiently understand Pakistan? How does it look from the inside?

Working with many activists, I recognise that both Europeans and Americans are locked into their own context. When it comes to South Asians in general, or Pakistanis in particular, I think they know little.

We were discussing before that, contrary to Western opinion, Pakistan is not a conservative society. You know personally that I am an independent woman and my opinions do not come from some novel. Pakistan is not a stone-age conservative society. Okay though, politically we are poorly governed. But we know a lot more about other contexts. We know Iran, Saudi Arabia, Qatar. We know European countries, we know the United States, but they don’t know us.

I am sometimes offended when people ask us on trips if we are Indian because of the clothes we wear. We have a lot in common with India, but we are different. I can tell if someone is German or Dutch, but they don’t know if I’m Indian or Pakistani. If somebody lives in Europe and has never travelled, I can accept their ignorance.

But if someone who has travelled a lot doesn’t know the difference between Indian and Pakistani cuisine or culture at all, then I am offended. Pakistan may be conservative and Islamic, but Europeans do not realise that it is not about religion. It is the political interest and environment, partly imposed by external forces based on global and strategically involved actors and stakeholders. We have never had the space to make our own decisions. I don’t appreciate when world calls Pakistan is a land of extremists and conservatives. There is enormous diversity here. We have a managed democracy, but that is not all. The country is ruled by an elite, but that does not reflect the opinions or the lifestyle of ordinary Pakistanis.

Yes, the country is badly governed, but that does not characterise us as a nation of bad people, we are only 75 years old, we are growing, we are learning, we are evolving. Women of Pakistan are inspiring, forward looking progressive and they are doing their best to uplift the country.

You can follow the activities of the Forum for Dignity on Facebook at Forum For Diginity Initiatives.