The Pearl necklace is very….hetero

We met in Tallinn and now we’ve been married for almost five years. Timothy and I – complicated navigation between spaces and ideas, making and interpretation, relationships with the environments and ourselves. Timothy’s domain is art jewelry, mine gender relations. Locating these two on the ground of social interaction and power relations has given us long conversations. On a snowy Sunday, we talk about how masculinities are treated in art jewelry, especially in Timothy’s own work.

Christian Veske-McMahon: In the Western contemporary contexts, jewelry and the act of adornment are quite often seen as a feminine. At the same time, historically speaking, adornment has been always a way of displaying male power. How do you explain this quasi-contradiction?

Timothy Veske-McMahon: As a male form of adornment, and in terms of how you’re phrasing it, as part of a power dynamic, jewelry has been connected to currency throughout recorded history. Jewelry has a technical history with carvers and bead-makers, minters and coin-makers, so it’s always been in proximity to wealth, power, and status… And whether or not it’s attached to a body or it’s hidden beneath floorboards or within clothing, the stitch that holds clothing together or stitched onto clothing, there’s always been the connection between the holding of wealth and the display of wealth to increase status in society. We could talk of crown jewels, livery badges, collars and medallions and the brotherhoods and fellowships – are always connected with jewelry objects, whether they’re a brooch, whether it’s a medal, a coin, a badge, a token…all of these things, these expressions of male hierarchies, are always entering through precious objects with a relationship to the body.

If we think specifically about the male body wearing jewelry, in the modern era it is not a popular thing. The male body has limited acceptable formats of jewelry. We have cufflinks, we have tie tacks, we have lapel pins, and depending on the generational demographic or where this person is or where they’ve come from, maybe a man wears earrings, maybe a man wears a ring or a pinky ring. In America, if we think about men who wear jewelry or wore jewelry conspicuously in the last 100 years, we might think within the organized memberships formed around religion, fellowship, profession, cultural identity, or criminal activity…it’s not just the wealth they’re displaying, they’re also displaying rank and status within traditionally homosocial power structures.

Indeed, as in masculinities’ research, “hegemonic masculinity” is one of the popularized ideas that link the dominant masculinity something others aspire to. Raewyn Connell, one of the founders of the concept, talks about the prevalent corporate or business masculinity. This sort of business masculinity leaves very little room for personal adornment or expressing identities other ways. You also tapped into where jewelry or the act of adornment is allowed within the power structures, but also in some subcultures, which are quite often based on the fact that you are able to identify the subculture based on how what they are wearing, or how the people look, or the way they talk.

Now, you started to talk more about American power structures, but maybe bringing this a bit to the subcultures…what does the adornment act mean there?

Well, it depends. Certainly, men are wearing jewelry in western subcultures. Often it’s tied to typical popular subcultures based on things such as musical taste, style of clothing, the things that people do during the identity-forming periods to differentiate between peer groups and from preceding generations. Within that, jewelry is a subversive countercultural tool, we can think of hip-hop and punk culture, of the act and placement of piercings alongside how we consider tattoos on a male body. But we can think of male body piercings and jewelry adornment as a taboo subject in the majority of the western world.

So if a businessman strays outside the lapel pin, cufflink, tie tack, or the wedding ring – these normative locations or positions of jewelry – and he comes to work with a very expressive necklace, or he comes to work with earrings, not just a stud or a diamond stud but dangling earrings, or he comes in with a pearl necklace, that becomes a subversive act. We wouldn’t see that…we might see that in fashion and in other creative industries that value idiosyncratic gestures, where it passes because it shows you stand apart from normative positions, that you don’t fit in, that you are a taboo-breaker.

Is that the moment where jewelry becomes queer?

Well, it could be. It could be. I would say that the object itself is not queer. But in terms of ecology – and this is where I’m really interested – this line between, what we think about jewelry as sociological phenomena, we can also think of jewelry, especially contemporary jewelry, as ecological phenomena, and it interests me to think that pearl necklace is very…hetero. If a businessman wears the pearl necklace to the board meeting, the necklace has not been queered. That pearl necklace is still a very ‘straight’ object. Its trajectory hasn’t changed.

But the subject of adornment has been queered?

Indeed, the male body and the identity of the person has been queered by that necklace, especially in that ordered setting. What does jewelry offer in terms of a sociological aspect or whether it’s an ecological aspect, whether it’s just between people, or it’s between people, objects, and environment, and that is where the idea of queer jewelry, what is jewelry or what becomes a queer jewel is very important, because it is contingent with environment.

Timothy Veske-McMahon. Teem VI

There is also a difference between what we consider traditional jewelry, such as fine jewelry or precious jewelry, and what contemporary jewelry is, which is a very small niche of the art and design world. It’s largely an academic product, though there are galleries, collectors, and those who appreciate and wear it, it’s still people who have a proximity to its origin. So it’s actually a pretentious claim on jewelry within everyday culture, and I think most contemporary jewelry as objects could be considered queer jewels. Because they are a…I don’t want to say perversion, but they are a shifting turn from normative jewels, the normal jewels in society, almost every piece of contemporary jewelry is a queered form of that. ‘Queer’ not necessarily in orientation, but ‘queer’ in form, movement, structure, scale, placement, experience, and so on.

Michael Kimmel has phrased this tension of masculinity within men themselves by pointing out complex relations between masculinity, male socialization and homophobia. He says that in America, in present-day America, for men ‘being a man means not being a woman.’ In my view, this refers to internal misogyny in men. The mainstream gay culture has quite often appropriated heteronormative views on gender. Fantasized straight male body is an ideal and perceived femininity seen as something undesirable. Has the gay community lost its ability to live transcending the normativity? In contemporary times, has jewelry lost its potential to thrive among the gay community?

Thinking on this tension within men themselves gives me a funny thought. I don’t know if this is only an American thing, but when I was younger, it wasn’t as common for men to have pierced ears, or if they were, depending on the subculture, it was only appropriate to have one ear pierced, but it was important which ear it was. Because you couldn’t have two ears pierced, that would be queer. You could have one ear pierced, but even whether it was the left or the right ear, would allow you to pass in only one of those two places. So that spectrum doesn’t just exist in theory. I mean that spectrum literally exists within the rules of adornment. It passes across the face from left to right.

I remember reading about it when I was 15. This was described as a signal for other gay men. Was it a way of recognizing each other?

Yes, and there are other aspects of that kind of signalling which aren’t related to jewelry, as well, but I would say part of it was myth created from paranoia, from normative culture and the need to label and identify, from wanting people to not fall on a spectrum but be fixed in place. Was the myth co-opted as signal, or did a sub-cultural signal escape?

We have been talking quite a bit about wearable jewelry. You, on the other hand, are also known for your work and thinking about contemporary jewelry. There are several well-known and interesting contemporary jewelers whom you suggested me to look at whose work touches upon the tensions around masculinities. Some of the works of Andrew Kuebeck and Keith Lewis caught my eye. These examples are direct with the aim of breaking taboos. Phallocentric, if you wish. Your work, in my eyes, treats masculinities differently. There are layers to it, which one needs to penetrate to understand the complexities of masculine expressions. Why, do you think, when contemporary jewelry treats masculinity, it leaves so little room for interpretation?

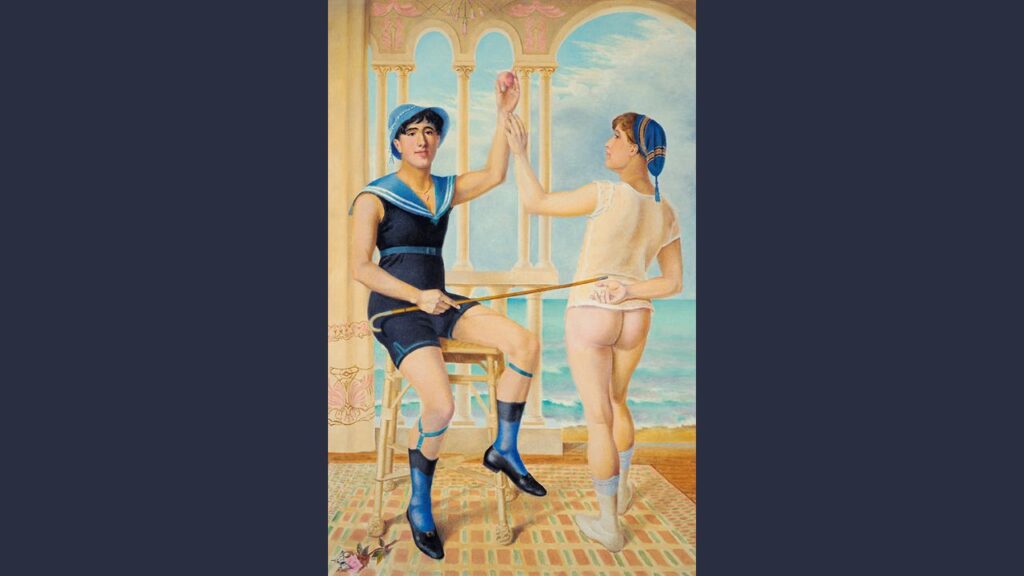

Andrew Kuebeck. Sailor

Yeah, well I mean, it’s a very good question. We could think of it in terms of the obscene, taboo, the lowbrow, or a kind of sardonic retribution but to do that would also categorize what the depiction of the male body is in those environments, with the point being it actually isn’t obscene and it is hidden by society.

Some artists, like those you’ve mentioned, are in more direct dialogues with topical culture…the straight male body and the queer male body, the clothed body and the naked body, the gazer and the gazee..subject matter as it is perceived as binary. In that respect, it is successful when shocking or spectacular and exposes averted perspectives to reveal what is beneath to the topmost surface.

Kuebeck’s work is also in reference to photography and portraiture and I would say is most activated when tapping into camp aesthetics. I’m actually having this funny thought right now connecting Kuebek’s work to this iconic piece of late 60’s American studio jewelry by Robert Ebendorf called “Man and His Pet Bee.” It is an assemblage of found objects into a brooch with an old tintype portrait of a man with a pressed-metal bee over his groin, its plump abdomen positioned suggestively between his legs… real heteronarrative but there’s a connection there.

I see Lewis on the other hand as appropriating the hegemonic sentimentality within traditional jewelry materials, techniques, and formats to reframe and present queer narratives. It’s kind of a reintroduction of ancient Roman graffiti to neoclassicism.

In my own work, I am not injecting preconceived identities. It coming from a place where it is an expression of a questioningly multi-layered identity, that isn’t trying to communicate with this perception of social structures or expectations of a body or adornment. With both types of work there is a relational question of what body wears it, what identity owns it, and who they come in contact with. It’s just as likely that someone could…it could be a totally normative female body wearing a piece of Kuebeck’s work because they appreciate the sentiment or the artistic value of it or they just think it’s beautiful, right? It could also be a queer man who wears it into a board meeting. Or maybe he just wears it on weekends when he’s not in the rigid structure and expectations of a corporate office. We don’t know.

That leads us inevitably to gender as performance. Masculinity as a performance of a series of acts.

Is it possible to describe adornment, not as performative?

This is my question to you.

I can’t think of an instance where adorning the body is not part of a performative act. Adornment stipulates that it’s not for a functional reason, it’s not like clothing, it’s not keeping me alive on a cold day, it’s not protecting me from the sun.

Except, if you think about Tobias Alm’s work and the essay about the workers’ belt? He argues that the workers’ belt is an object of adornment, yet it is also functional. So it has a function other than making a person more beautiful.

Well, I think perhaps the workers’ belt, like many things, is transitional. It ceases to be functional when it leaves the working environment and is reoriented as adornment…I mean it’s almost a type of drag isn’t it? Or is it a straightening device? In queer culture we might consider the castro clones and the appropriation of blue-collar working identities to not only safely pass outside the neighborhood but signal to their community members. Those pieces of Alm’s…I’m thinking of them as trans-objects, not in terms of gender but in this binary between the functional and the decorative.

Maybe it’s not interesting to you…but it’s interesting to me as a jeweler, to think about what is the distinction between style, fashion, and trend in pop culture and clothing, the adornment of the body with garments and then of jewelry, because jewelry has always been…it’s a type of accessory and there’s a question of whether it’s accessorizing clothing or whether it’s accessorizing identity.

Timothy Veske-McMahon. Borne XIII

A lot of your work deals with issues that relate to home and longing, and it gives a bit of a different perspective on masculinity in contemporary jewelry. Where does that come from?

I think it comes from this slippage between…the expectation of what exists in popular culture, and what is the reality of an identity, of a history, of a desire. It comes from that act of trying to locate and orient oneself within cultural references. Attempting to identify which expectations are of external origin and which come from an internal place.

I think it also comes from being conscientious about jewelry, my role as a maker of jewelry, and not as the wearer or the owner. I think the way that I see myself as a jeweler, is that I am in conversation with the person who ultimately decides to wear it. It’s a collaborative act, this performance, this adornment, this subversive, queer thing, it’s a collaboration with someone else. So it has to exist in this open place that someone else can wear, someone else can own it, it can be added to someone else.

I’m thinking now about your work from series “Borne” and “Teem”. It was one of the times I could be present for one of your openings. I remember very well at the opening of the exhibition when people realized that one of the brooches that looks like a piece of bread, that you used your chest hair to cover it with, that immediately created a lot of buzz around this specific piece. Why do you think that happened?

It happens because people are a bit surprised and have to figure out whether they’re comfortable with the idea that it’s actually like body hair, and it wasn’t just body hair, it was chest hair. So I think it would also be different if it was images of the hair from the top of my head or my beard hair. Arm hair is even different from chest hair, chest hair feels…how does someone normally experience another body’s chest hair? It’s normally in a moment of intimacy. So when someone is confronted [with] that, especially in that public situation, they have already performed with the piece, they have looked at it, gotten closer, been interested, and then find out they accidentally had this moment of intimacy with a body they normally wouldn’t.

Another aspect is that it’s not just chest hair, it’s my chest hair, it’s identifiable as a person. So it’s also this exposure, at that moment I’m shirtless and possibly also transported to a different room. Maybe it’s the bathroom or bedroom, the living room, but it’s certainly not the gallery space, and normally not the street with a stranger, even if it’s someone who’s interested in art and in contemporary jewelry.

Timothy Veske-McMahon. Teem-III

You yourself don’t wear very much jewelry?

I wear two pieces…almost every day.

And they’re very modest!

And both in very normative places. The ring finger on my left hand, which as you know is my wedding ring, and on my ring finger on my right hand, I have a very plain plate-like signet ring. It is actually from an idea-based project of another jeweler, but it’s very passing. My wedding ring may not be so passing, it’s a little different for a wedding ring, but my signet ring, you can’t get more passing. If it was on my pinky it could be a mob ring.

Why is that?

You know, I’ve been in debate whether or not I would look good with pierced ears, if I could pull it off. I think it’s just a matter of – are you an actor? Are you a performer? I mean, if jewelry is this performative thing, not all of us want to get on the stage. Some of us are engaged in prop-making or the stage direction for this performance playing out on the streets. Or playing out on the academic pages, or playing out wherever it may be. It could be in Vogue magazine. But I don’t think I’m so much…I’m not the performance artist.

Butler would disagree here! We all perform our genders constantly.

Well, my main stage is a jeweler’s bench.

In 2018 Feministeerium is focusing more on different men and masculinities. We are dealing with questions like what does it mean to ‘be a man’? And what does that have to do to be accepted as ‘real man’? What are the harmful effects of toxic masculinity — the set of standards our society holds for men that end up damaging both their lives and others? Here is a quick way to catch up the articles in the issue (in English, in Estonian).

This publication has been produced with the financial support from the Nordic Council of Ministers. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of the coordinators of this project and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Nordic Council of Ministers.