How Vienna focused on gender in urban planning

We live in diverse communities comprised of many different types of people. This diversity not only enriches the life of a society as a whole but also reflects the colorful reality. And, of course, it comes with a variety of needs and interests that require accommodation for a flourishing co-existence. For too long, urban planning has been male-centered and ignorant of many of those. In this article, Stefanie Blümel looks at how the city of Vienna has attempted to become more inclusive by applying gender mainstreaming in its urban planning processes.

This article uses the terms “men” and “women” to highlight the differences between gender roles in urban planning, where men are all people who define themselves as male and women are all people who define themselves as female. Non-binary, gender-fluid, and agender people are not to be excluded when designing public spaces, but the specifics of their needs have not been as well researched yet.

Why is there a need for diverse perspectives and considerations in urban planning?

What is gender-sensitive urban planning?

“At least half of the population is female and has different lifestyles and needs; we need to start recognizing them”. – K. Schechtner[

In principle, gender-sensitive urban planning centers around equally prioritizing the everyday lives of women, men, and non-binary people. Additionally, the needs of people of different age groups and financial status should be taken into account. There is a special focus on people who might otherwise be disadvantaged or neglected during the planning process. The aim is to reflect diversity in urban spaces and ensure that no needs or groups are left unattended, thus securing equal opportunities for achieving a higher quality of life (Irschik 2013, p. 17).

However, recognizing that a city is used differently is also an integral part of gender-sensitive urban planning. Some use the city just to commute and get to work; others use different shopping opportunities, big or small, luxurious or affordable; some enjoy nature and green spaces to relax or engage in physical activities. Younger people may use more leisure facilities and public amenities, such as cinemas and libraries, children need opportunities to safely play, develop, and learn, and tourists are mainly interested in cultural activities and easy access to them. This is just a small sample of the different interests and needs that cities are faced with (Magistrat der Stadt Wien, MA 18 2015).

We know what is good for everyone…?

“Men have commissioned

Men have financed

Men have planned

Men have built.

And in some parts of the globe, it is still men who use and occupy the public space of the city.

To what extent will the city of the future be tailored to the wishes and needs of women?” – K. Schechtner

Historically, upper-class male architects have largely centered urban spaces around their own needs, neglecting to recognize the needs and interests of other groups. Therefore, the city of Vienna pursues the approach of “putting oneself in different shoes” to get exposed to a wider specter of urban requirements.

More often than not, urban planning considers only the needs of so-called “average” people (men), which could and does often result in other groups facing logistical difficulties or compromised safety. For example, the rate of traffic light changes on busy intersections may leave some pedestrians in a disadvantaged position: while for an average person, 10 seconds might be enough to cross the road, for others it may be impossible due to age, physical disability etc. These groups are already vulnerable in traffic, and failure to account for their needs increases the risk of accidents and injury even further (K. Schechtner 2022).

Whose Public Space is it? Women’s Everyday Life in the City

Illustration: Stefanie Blümel

The City of Vienna has recognized the presence of these diverse needs, especially the ones based on prevalent gender roles, as early as 1991. It drew attention to the needs of women in the city with the exhibition “Whose Public Space is it? Women’s Everyday Life in the City.” and established the first Women’s Office in 1992. In 1998, the first office for women-friendly planning and building was established in the city of Vienna, with the task of integrating the needs of women and girls into mainstream male-oriented urban planning (Irschik 2013).

To ensure participation in social life for all, there is a need for consumption-free meeting places, clean toilets, and low-threshold or barrier-free facilities.

The 1991 exhibition showed eight daily routes of women and girls, illustrating the diversity of everyday tasks, and hence the different needs. It demonstrated that the streets are dominated by men, with women often feeling unsafe driving a car or riding a bicycle alone. This also demonstrated the behavioral differences between men and women in the city. Focus was also drawn to “anxiety and comfort spaces”: where women and girls feel comfortable and where unsafe. The exhibition explored how to identify such spaces, and what the possible underlying reasons might be. This was the first time such attention was drawn to analyzing the city space from the point of view of diverse needs (Drey 2022).

Why do street names matter?

The remanence of male-centered urban planning can still be seen in street names in Vienna, as the majority of them are named after men. However, the city of Vienna has set a goal of balancing it out by assigning female names to the streets in the new districts (Drey 2022).

We live in a society full of patriarchal structures that are so widespread that they are sometimes not even recognized as such. Through consciously applying “small” changes, however, these structures can be made visible and action can be taken against them. In addition, women need role models, of which there are many, but who are often hidden behind men. There are many female pioneers and important personalities, but they often receive less attention than men (K. Schechtner 2022), (Drey 2022).

Gender-sensitive park design

“At some point, female youth disappear from parks” (K.Schechtner 2022)

Observations and studies indicate that parks were dominated by male youth, while female youth have been disappearing from such spaces. This led to a pilot project in which girls were invited to participate in the park design process to ensure their interests being represented. Since 2009, there have been general guidelines for gender-sensitive park design. The main question was what do girls and young women want to do in a park and what’s important to them: playing volleyball, having places to sit and talk, safe areas, clean toilets, swings, soccer and basketball courts.

Every new park is designed per these guidelines to provide a wider range of social groups an equally comfortable and accessible experience in the parks (K. Schechtner 2022)

Another project of the City of Vienna was the sidewalk project in the Mariahilf district. It involved the construction of wide sidewalks, monitoring and readjustment of traffic lights, improvement of safety, provision of accessibility, definition of safe spaces, and the addition of lighting.

Women’s Workshop City I

Illustration: Stefanie Blümel

“We face the challenge of transforming our cities quickly, but we should see this as an opportunity to make a difference.” (K. Schechtner 2022)

The main objectives of the Women’s Workshop City I model project – a housing facility at Donaufelder stresst 95-97 in the 21st district of Vienna – were to facilitate housework and family life and to create an environment in which residents could safely socialize at night. The goals of the model project were to facilitate household and family work, promote neighborhood contacts, and create a living environment in which the residents could move about safely, even at night. As part of the expansion of the city of Vienna, this project was the largest construction project in Europe to be planned by women and to meet the standards of women-friendly housing and urban development. Between 1992 and 1997, the Women’s Office of the City of Vienna planned 357 apartments on an area of 2.3 hectares, designed by four architects in collaboration with a landscape architect.

Another goal of this model project was to increase awareness and visibility of women architects, both in the public and the professional world.

In the Women’s Workshop City, there are various open spaces with a high quality of living, with community facilities, infrastructure such as shops, kindergartens, doctors, and a police station, naturally lit underground garages and corridors, staircases with residential quality and innovative basic solutions.

The project produced approaches and solutions that can be transferred to other housing developments. The Women’s Workshop can be described as a successful model. (Stadt Wien, Magistratsdirektion – Geschäftsbereich Bauten und Technik).

How does it feel to be a woman in Vienna?

In 2022, Vienna surveyed women to find out how they feel living in Vienna, what their needs are, and what they are worried about.

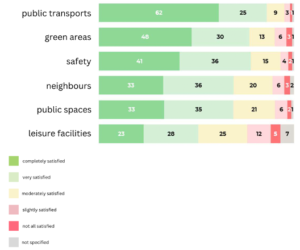

How satisfied are the women in Vienna with their living situation?

This chart shows that while there is an overwhelmingly high level of satisfaction with one’s own dwelling and living environment, there is also a desire for more public amenities: private open spaces, or common areas in the housing complex.

The feeling of safety in residential areas is generally high. Vulnerable groups, women with physical or mental disabilities, single parents, and women on low incomes most often feel unsafe. Both the presence of shared spaces and the level of safety are closely linked to social status.

Does the city feel woman-friendly or rather hostile?

Almost half of the respondents (45%) perceive the climate in Vienna as (very) pro-women, 39% as neutral, and 10% as (very) anti-women.

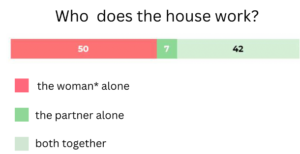

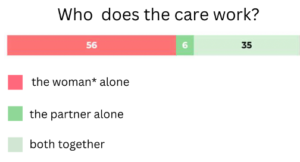

Looking at the domestic and care work chart, it is clear that 50 percent of women do the housework alone, and 56 percent do the childcare alone. And even in these cases, most of the women are also working in another job as well.

When asked about the general life in the city, many women felt it was too crowded with buildings and too car-centric. A desire for women’s needs to be more visible in society was also expressed. To ensure participation in social life for all, there is a need for consumption-free meeting places, clean toilets, and low-threshold or barrier-free facilities. The importance of safety in public spaces was also repeatedly stressed.

In particular, there was a focus on better lighting of streets and parks, the implementation of designated safe spaces, and an increased presence of law enforcement officers (Ergebnisse der Wiener Frauenbefragung).

What can every city do?

Men have put a lot of attention onto bigger projects, buildings, and urban spaces. Thus, many small residual spaces have been neglected or not considered. These are the spaces that can now be our opportunities to create something new for everyone.

The benefits of an equitable city extend to everyone, not just those for whom the special accommodations have been implemented. For example, a wider sidewalk, designed to fit a person with a stroller, also becomes safer and more comfortable for moving in a wheelchair, carrying large shopping bags, or carrying furniture (K. Schechtner 2022).

Men and women?

One might think that in 2023 there would be no need for specialized initiatives to ensure that women feel comfortable in a city, or that they require any specific accomodations. One might assume that a city can be built gender-neutral to suit everyone. One can even think that a female-friendly planning structure would be “unfair” to the male population because they do not get this additional attention. However, this is not the case, as statistics show that there are still huge differences between men’s and women’s lives in a given society. That is why it is necessary to focus the women’s place in the world, which has always been somewhat forgotten or repressed.

At some point in the future, however, it would be desirable that such a focus on one gender is no longer necessary, but that a general focus is placed on the development of human beings rather than on individual dominant genders. But until systemic gender inequality that leads to these gender-specific urban dwelling styles is dismantled, additional attention must be paid to the needs of marginalized groups, including women.

Sources:

- K. Schechtner (2022)Frauen Bauen Stadt – The City Through a Female Lens Youtube Video

- Drey, Christl (2022): Eine Stadt für alle … wirklich alle! Youtube Video.

- GenderKompassPlanung.

- Irschik, Elisabeth (Hg.) (2013): Handbuch Gender Mainstreaming in der Stadtplanung und Stadtentwicklung. STEP 2025 Stadtentwicklungsplan. Wien: Stadtentwicklung Wien MA. 18 – Stadtentwicklung und Stadtplanung (Werkstattberichte / Stadtentwicklung, 130).

- Schechtner (2022): Frauen Bauen Stadt – The City Through a Female Lens. IBA Wien (Regie).

- Magistrat der Stadt Wien, MA 18 (2015): Stadtentwicklung Wien-Lebenswerte Stadt. Youtube Video.

- Stadt Wien: Magistratsdirektion-Geschäftsbereich Bauten und Technik: Frauen-Werk-Stadt I – Alltagsgerechtes Planen und Bauen.

- City of Vienna: Parks – ways to implement gender mainstreaming. https://www.wien.gv.at/english/administration/gendermainstreaming/examples/parks.html. City of Vienna.