The “fascist femboys” of Baltic German artist Elisàr von Kupffer. Interview with historian Ben Miller

Ben Miller is a writer, member of the board of the Schwules Museum in Berlin, co-host of the popular podcast series Bad Gays and co-author of the book Bad Gays: A Homosexual History (2022), dedicated to “evil and complicated queers in history”.1 He recently defended his doctoral thesis in Global Intellectual History at the Freie Universität Berlin. His dissertation – titled In Search of Lost Time: Primitivist Homomythopoetics and the Self-Invention of the White Gay Man – traces the racist legacies of the gay liberation movement, from Weimar-era Germany to 1970s San Francisco, California, through examining the strategic adoption of primitivist tropes by some of its key figures.

On 5 June, Ben visited the Kumu Art Museum exhibition “Elisarion. Elisàr von Kupffer and Jaanus Samma”2 to give a lecture on the curious position that Kupffer assumes in queer history, highlighting some of the seemingly contradictory aspects about his figure that trouble people when they search for inspirational queer narratives of the past. We revisited some of these ideas in conversation.

Historian Ben Miller at KUMU art museum. Photo: Maria Lota Lumiste

Let’s talk about Elisàr von Kupffer. Who is he? What’s he famous for?

So Elisàr von Kupffer is a– It’s funny. I’m actually looking for the right noun, right? I don’t know whether to call him an artist or religious leader, an activist, a fascist. He’s all the above.

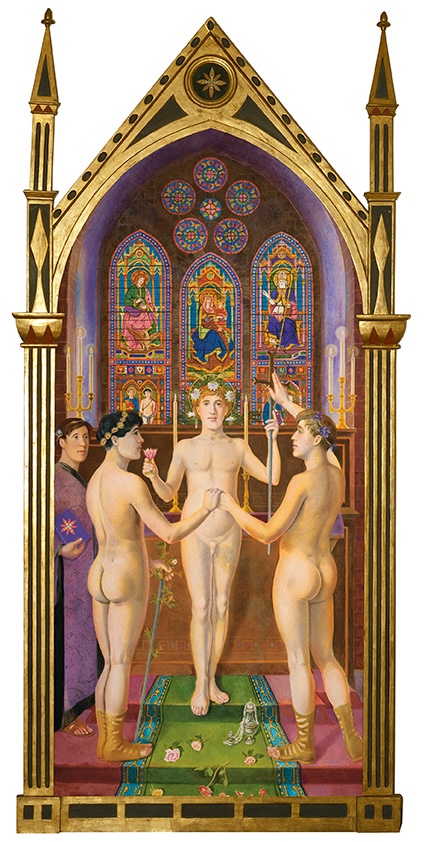

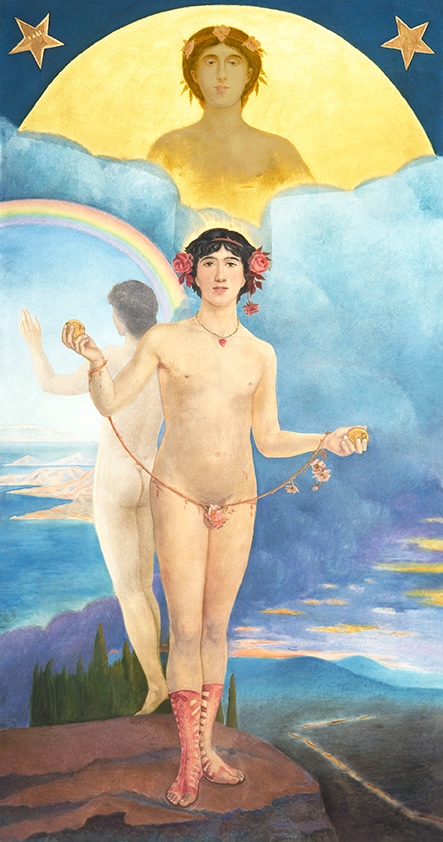

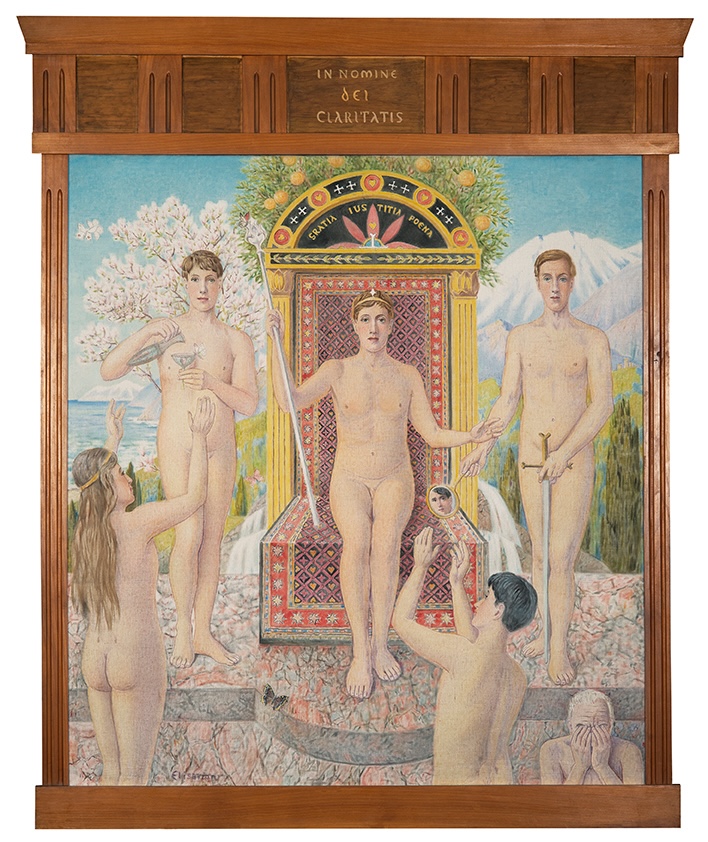

But he’s a man who lives between 1872 and 1942. He’s born in what is now present-day Estonia, as part of the class of Baltic German overlords there, and throughout the course of his life, he assembles the first ever anthology of gay literature, which is called The Love of Favourites and Friendly Love in World Literature, which is published in Berlin in 1900.3 He creates a new religion called Klarismus or Clearism, which combines medievalist and Christian iconography with ideas about that kind of universal, transcendent spiritual androgyny that he gets out of readings and misreadings of Persian literature and of the classical era. He creates a series of artistic works culminating in the 30-metre cyclorama painting called The Clear World of the Blessed,4 which depicts the Claristic utopia in which many naked androgynes – all of which bear either his face, the face of his life partner Eduard von Mayer, or the face of a favourite local model, “Gino” Luigi Taricco – are depicted.

His work throughout his entire career is informed by a biological racism that understands human cultural output as being rooted entirely in climate and race, which are understood to be linked. For this reason, for example, he settles in Italian Switzerland because he understands it as being a bisexual climate: there’s the Mediterranean homosexual climate and race type, and in the German Alpine, heterosexual climate and race type.5 And so, he’s found in Ticino6 a bisexual climate. That’s maybe a more humorous example of this biological determinism. But this also leads him to subscribe to antisemitic conspiracy theories, to be described by Nazi officials as a devoted hater of the Jews, and to several attempts to collaborate with Nazi politicians in order to secure state support and funding for this artwork and for this religious project. He fails, but not for lack of trying, including several extremely warm letters written to Adolf Hitler at the end of Kupffer’s life, where he really praises Hitler, his political project and identifies them as political allies.7

So Kupffer is a really complex, controversial and strange figure. I hope very much that this article is being published alongside some images of his artwork as well, because you really do need to see this art to believe it. It is, I like to joke, mercifully inimitable. It’s really something.

Elisàr von Kupffer. The New Covenant. 1915–1916. Centro Elisarion, municipality of Minusio

I will insist upon this, as well. But let’s first discuss this collection that you mentioned, this anthology of homoerotic literature called The Love of the Beloved and Friendly Love in World Literature.

Yeah, Lieblingminne und Freundesliebe in der Weltliteratur.

At that time, the homosexual emancipation movement in Germany was picking up and it was quite a topical publication. What position did this work have in that context? Was it very impactful or did it remain in the background?

It was extremely impactful.

In around 1869, the word “homosexual” is coined in the German-speaking lands and the late 19th century is a moment when medical science is trying to understand various, what it understands as, sexual pathologies, homosexuality being one of them. This is why the word homosexuality, the concept of homosexuality is actually coined and invented before the concept of heterosexuality: because the science starts by looking for what it thinks are problems and only then gets around to defining the normal against the problem.8 Then, by the turn of the 19th and 20th century, people who find themselves classified medically are starting to search for some sort of positive, self-originated or self-developed understanding of what they are that exists independently from, or that can help combat, diagnoses or criminalisation.

In the German-speaking countries, in 1900, there are already two streams of thought developing. One of them is emblematised by the German Jewish sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld, who in 1897 founds the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee. Hirschfeld is himself a sexologist. He is never actually publicly out, although I think it’s assumed by many people, and he develops an understanding of homosexuality as one of many possible, what he says, sexual steps between the heterosexual man and heterosexual woman: that there are an infinite number of potential variations of orientation, of sexuation, and that all of these variations, to the extent that people are able to live with them, are benign – so accepting the idea that this is a medical difference, but saying it’s not a medical difference that needs to be cured. The motto of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee is “Through science to justice”,9 right? So, a scientistic understanding.

Elisàr von Kupffer. The ascension, 1911. Centro Elisarion, municipality of Minusio

Kupffer’s book, however, is published in the book series of Adolf Brand, whose magazine Der Eigene began the masculinist stream.10 He is very much associated with the group of people who reject science. They really reject diagnoses, they reject these medical categories, and instead look to human history and, specifically, to – and I say this very intentionally – Great Men. They say “We’re not a medical category, we’re not a diagnosis, we’re not something in between. Let’s look back at human history to Frederick the Great, Alexander the Great, Michelangelo…”11 They look back to evidence of homoerotic behaviour in Western civilisation from the classical era all the way through to the 19th century, where it did exist. Today’s gay and queer identities are not particularly old, but same-sex erotic behaviour is reported in every human society in all of human history. And so, they find this evidence and they marshal it into a theory that says that gay men are uniquely equipped to be leaders and heroes of a needed social transformation.

On the one hand, this actually is a crucial part of helping gay men in general develop a cultural and social subjectivity that exists outside of categories of medical diagnoses. On the other hand, they are often extremely misogynistic. Their interpretation of the relationship between homosexuality and heroism is that women are a drag on human progress and the men who reject women can go further and do more because they’re not dragged down by the evil feminine. They’re also often extremely antisemitic. Jewishness and femaleness are often constructed together as negative influences on especially the German national project.

These two sides were not, at least until later, diametrically opposed. So, despite the fact that there are many masculinist publications, who right from the beginning are extremely critical of Hirschfeld’s work – sometimes criticising the idea of medicalisation, sometimes falling into really vile antisemitism –, Kupffer, for a while, is writing relatively friendly of Hirschfeld, even though he disagrees with him. He talks about Hirschfeld’s work being really important to help understand these complicated sexual problems. And so, while there are these two streams, it’s important to think that there’s also always a conversation between them, a back-and-forth. Both of them are complicated, both of them are ambivalent and both of them are really important parts of the construction of the sexual subjectivities that we have today.

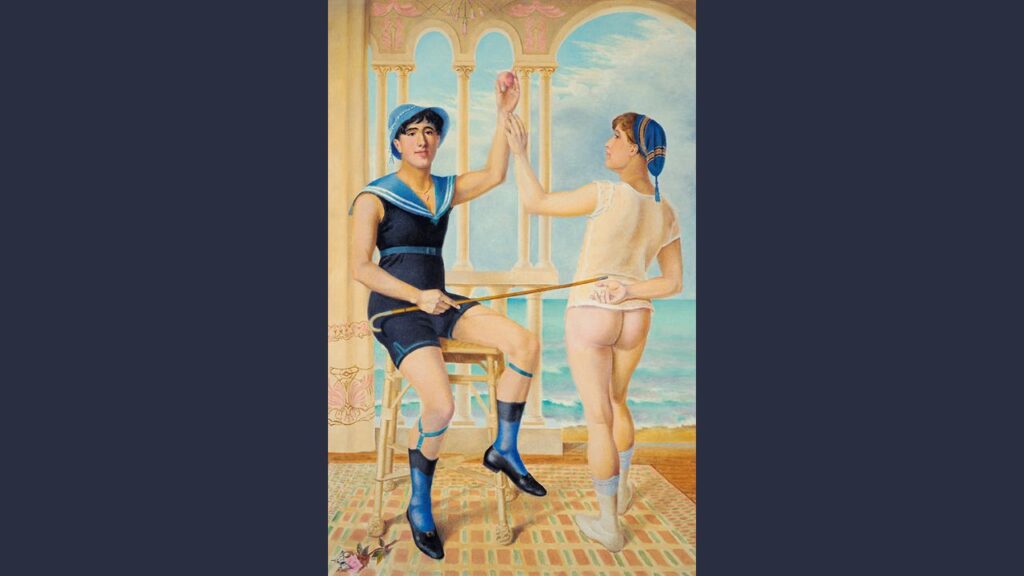

Elisàr von Kupffer. The disarmament, 1914. Centro Elisarion, municipality of Minusio

You mentioned Adolf Brand. He was an anarchist, as far as I remember, into left wing politics, I’m guessing, ambivalently so. Where does Kupffer position himself on a political scale? Because the beginning of the 20th century is a time period where there’s a lot of political radicalisation.

It is. So, there’s left anarchism and there’s right anarchism, right? Masculinism is an anarchist tradition, but it is also, in some cases, a proto-fascist tradition. The only way that we can understand how both of those things can be true is by thinking about the tradition of individualist anarchism. People like Stirner [Max Stirner (1806-1856), a German philosopher and originator of egoist anarchism that prioritises individual self-interest – A.P.].12 And that’s where these people start to come in. Kupffer himself is rather hard to place politically. I don’t want to call Kupffer an anarchist of any kind, nor do I really want to call him a Nietzschean, although I think individualist anarchism and Nietzsche are both helpful in terms of placing Kupffer and understanding his relationship to the ancient world.

But Kupffer’s own political formation is really shaped by the experience of watching the Bolshevik revolution happen. His family and many of their family friends in that moment obviously lose a lot of status and power. He comes from the landed Baltic German class of pre-revolutionary Baltics. [Although Kupffer came from the nobility, he was not part of the landed gentry. His father worked as a parish doctor, with the peasantry as his main patients. The society in the Baltics was hierarchical, the nobility was diverse, and people of German nationality were looked up to regardless of their exact status. – Ed.]13

And so, he develops a real hatred of Bolshevism and that’s where a lot of the antisemitism starts to creep into his work. He writes a pamphlet called 3000 Years of Bolshevism,14 which is really quite something in terms of watching some of these Judeo-Bolshevik conspiracy theories be born.15

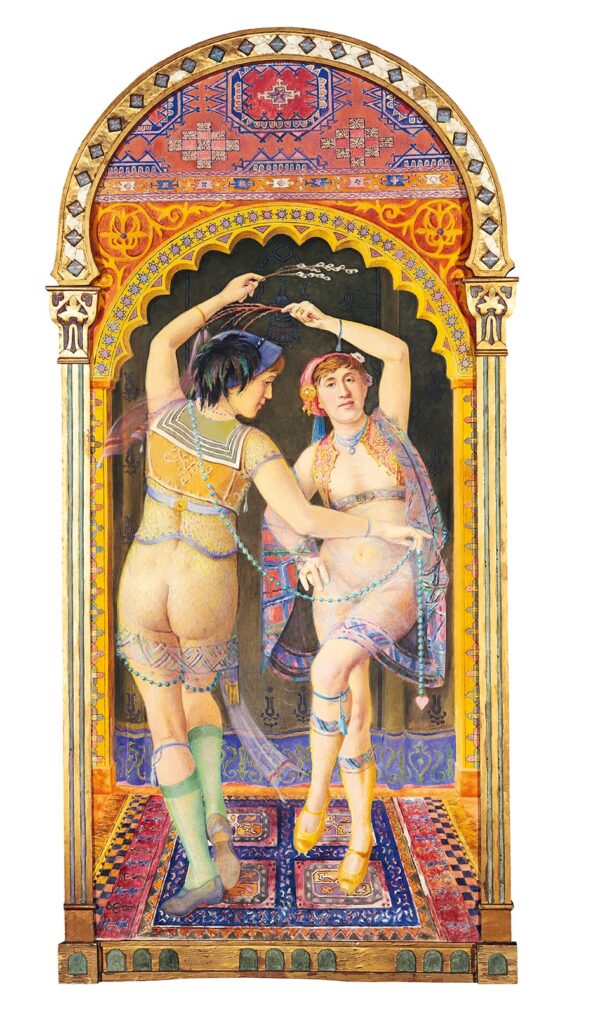

Elisàr von Kupffer. The dance in the temple, 1918. Centro Elisarion, municipality of Minusio

I’m wondering how Kupffer’s ideologies are reflected in his artworks. There is an interesting– I don’t want to say conflict… But when you think about masculinist art, you usually think about these very buff bodies, very masculine figures, but you don’t really see that in Kupffer’s works. How did he reconcile his misogynistic, antisemitic, fascist sympathies – that we commonly associate with hypermasculine imageries – with the soft and androgynous bodies that we see in his utopian Klarwelt?

Yeah, maybe Fascist Femboys would be a good title for this interview, because that’s who’s depicted in Kupffer’s work. It is complicated. Anyone who’s seen the work, as you mentioned, will notice an immediate problem with how I’ve been describing Kupffer’s politics until this point. If you read the introduction to Lieblingminne [und Freundesliebe in der Weltliteratur], which is all about how we live in a time where manly values are being oppressed by female supremacy, and then you see these artworks, you think: “Oh God, these are not the male bodies that I’m expecting to see even in terms of the history of masculine, if not masculinist, gay homoerotic art!” – right?

Another person who likes to put a lot of sort of identical looking figures in parks or in outdoor settings and populate scenes with them is Tom of Finland. But Tom of Finland’s bodies are very different from Kupffer’s bodies: his bodies are big, angular and muscular, with very large primary and secondary male sexual characteristics. But Kupffer’s figures are very androgynous. He settles on this figure of the spiritually transcendent androgyne as a force of spiritual renewal when he starts to develop his Klarismus religion in the 1910s. And what I think is really interesting about it is that it is as though Kupffer is mining femaleness for certain important characteristics that might be useful for this masculine future, but then discards the actual women and just brings those characteristics into the future in these beings who are, while androgynous, still always recognisably men.

I think there’s an interesting analogy to be drawn here with the way that primitivism not only in queer art, but also in other kinds of radical art and social movements, functions. If we’re looking at the minoritised being, whether that’s the racialised Other in the case of primitivism or the women in the case of in the case of what Kupffer’s doing here – if we look at that being as a source of commodities, or as a source of things that we might have forgotten as we became “over-civilised” as white Western men, then we need to go and find some of these impulses and then bring them into our present. But we’re not going to actually think about what makes life better for those people; we’re not going to actually bring those people into our political future, right? Primitivism very rarely imagines an actual political or aesthetic future for the “primitive”. It assigns that “primitive” to the permanent past. And Kupffer is doing something similar with women.

There’s also some really interesting thinking that’s been done about the ways that fascist German masculinity of that period – and this all comes from the theorist Klaus Theweleit16 – was really based on tremendously visceral fear and disgust of the female body, especially the working-class female body, as a source of unregulated desires and impulses and flows that were not properly contained within the rationally governed armour of the proper male body politic. And I think Kupffer, while he depicts a really different male body politic – a much more androgynous male body politic –, he’s still depicting this extremely rational control and governed place where everything is in its right position. And I think some of the same fears and disgusts of the sexual, as opposed to the erotic, or the ungoverned body are still really visibly present in his work.

Elisàr von Kupffer. The souls before their judges, 1937. Centro Elisarion, municipality of Minusio

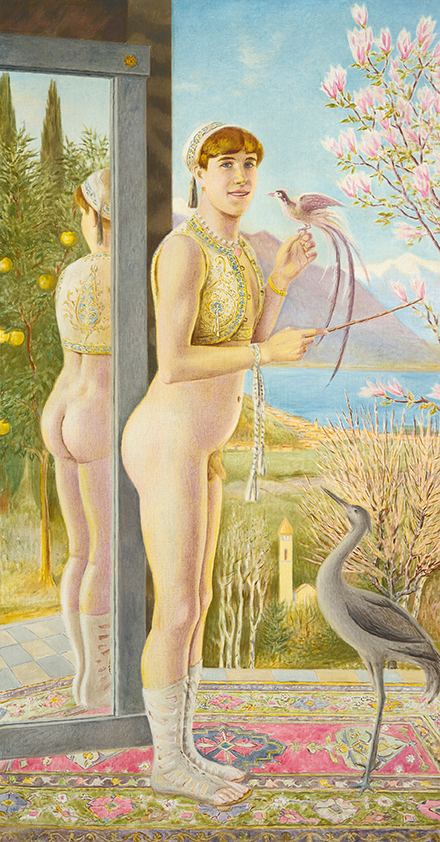

You can also see very specific Orientalist influences in his works. Where does he get this in terms of artistic designs?

His artistic influences are many. It’s important to say that his art has nothing to do with primitivist or modern art in the way that we think of like Picasso or, you know, people who had these kinds of influences. His art has nothing to do with that visually. Rather, almost like the pre-Raphaelites, he has the sense of a return to an earlier period of Western art history. He’s really interested in the painting of Il Sodoma.17

In terms of the Orientalist influences, he picks this up from a study of what is then called “Oriental literatures” in Saint Petersburg, which, at the time that he was studying, was where you wanted to go if you wanted to learn about these literatures and didn’t want to actually leave Europe – because Saint Petersburg had one of the largest collections of Persian manuscripts at the time.

Kupffer also gets a lot of inspiration artistically from travelling in Italy, like many gays before him, including very important trips to Pompeii, where he studies a lot of the murals and the things that were uncovered, and also trips to the Roman villa of the German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who was a classicist art historian and a very important figure in the proto-gay subjectivity formation in the German-speaking world.18 Kupffer has a realisation in Winckelmann’s villa, where he comes to the idea of this androgynous figure – the Araphrodite, as he calls it. Those are some of the artistic influences.

Elisàr von Kupffer. The bird seller, 1918. Centro Elisarion, municipality of Minusio

What drives queer individuals from the early 20th century to look at conservative politics and ideas of the primitivist past to envision a future? We know so many examples of this.

Well, primitivism is not only a feature of conservative politics – it’s something that can be politically ambivalent. So, I want to answer those two questions separately.

My research has mainly been about primitivism. My recently completed dissertation, which is called In Search of Lost Time: Primitivist Homomythopoetics and the Self-Invention of the White Gay Man, examines white gay men’s use of primitivism to construct positive identities outside of medicalisation and criminalisation. And what I argue in that research, is that this ends up baking a primitivist homomythopoetics: the poiesis, the creation, the invention, the fabrication of collective myth for white gay men bakes a lot of damaging and violent ingredients into the cake of the sexual identities that we have today. Sorry, it’s a tortured metaphor, but hopefully people will understand what I mean. It really is, I think, a search for radical alterity, a search for things that are other than the present. The idea of trying to think about ways to live other than the way that we live now is important and yet it also makes sense that in a world governed by violent, colonial and racist systems of production and exchange, many white gay men then and now will search in ways characterised by the exclusions that also produce their race and class.

The poiesis, the creation, the invention, the fabrication of collective myth for white gay men bakes a lot of damaging and violent ingredients into the cake of the sexual identities that we have today.

In terms of conservative politics, I think class position is a hell of a drug. People really like to preserve what it is that they have. In the case of someone like Kupffer – in the case of actually many people in the early 20th century – often an elevated class position was a ticket to having a relatively undisturbed life. Kupffer was able to have a house and he was able to live there with Eduard von Mayer, his partner, and he was able to buy a lot of canvas and a lot of paint to make his utopia and paint his pictures. Anything that was a challenge to that, like the Bolshevik revolution had been, was really threatening and became then the basis for a politics of resentment and reaction.

It’s crucial to remember that queer can also be ambivalent

I think it’s important to realise that queer is a– well, several things, right? It’s a collective noun. It’s a way of describing people who are Other to the sex-gender system or who help us understand the sex-gender system in different ways. But it doesn’t imply good. And I think one of the most damaging assumptions that circulate in queer studies as an academic field, but I think especially in the kind of pop queer conversations, is this idea of queer as being everything that isn’t normal, everything that we like, everything that kind of “fights the Man”. And I believe when we think that way, then we really get stumped by a figure like Elisàr von Kupffer because we don’t know what to do with them. Because you have someone who is indisputably queer for his time and place; you have someone who is Other to the sex-gender system advocating this very particular kind of androgyny. If Kupffer had painted big buff muscle-men, it would be much easier – in the contemporary perspective – to put the fascist politics and that in one box and understand it really well, as you said. But it isn’t and he didn’t. And that’s important because it’s crucial to remember that queer can also be ambivalent. It’s a description of being Other to the sex-gender system: you can be Other to the sex-gender system in ways that are really bad, and you can be Other to the sex-gender system without implying that you have radical or liberationist politics.

Elisàr von Kupffer in Creek costyme. Photo: Centro Elisarion, municipality of Minusio

Why is this topic of fascist queer people relevant? Why do we talk about those “bad gays”? Isn’t it easier to just, you know… shove them aside and pretend they never existed?

Easier, yes. But then you end up promoting some, I think, really boring, stupid and reactionary understandings of queer life and queer history, right? These things did happen. These people did exist. And I think we need to think about, as Jennifer Evans19 has said, our “bad kin” in order to understand how we ourselves might be complicit with structures of power and structures of violence and structures of evil. If we only think about queer people who were either perfect victims or heroic resistors, then we are writing humanity out of queer history. And I think that does no one any good.

Elisàr von Kupffer. Four-Horse Carriage in Jootme, 1890 and 1939. Centro Elisarion, municipality of Minusio

Find Ben Miller’s writing here: https://benwritesthings.com/.

- https://badgayspod.com/

- https://kumu.ekm.ee/syndmus/elisarion-elisar-von-kupffer-ja-jaanus-samma/

- The anthology contains classical texts from Greek, Roman and Persian cultures, more modern texts by, for example, Shakespeare, Byron, Goethe, Schiller, August von Platen and Paul Verlaine as well as Kupffer’s own poetry. See more on this in Liina Lukas’s “Élisàr von Kupfferi kirjanduslikust loomingust”: https://www.vikerkaar.ee/archives/30591.

- Die Klarwelt der Seligen (1919-1929). You can inspect the cyclorama in detail here: https://www.elisarion.ch/en/the_cyclorama/the_33_scenes_and_their_meaning/.

- The concept of the “Sotadic Zone” was developed by the British anthropologist and explorer Sir Richard Francis Burton (1821-1890). In the appendix to his translation of One Thousand and One Nights (1886), Burton elaborates on the “topographical details concerning pederasty, which I hold to be geographical and climatic, not racial”: he sees the areas belonging to the Zone as places with widespread homosexual behaviour among people, including the Mediterranean regions, South and East Asia, America, and the Pacific islands. For this, he blames the “the blending of the masculine and feminine temperaments”. Europe beyond its southern regions would fall outside of that area. Based on a similar understanding, Elisàr von Kupffer writes a pamphlet titled Klima und Dichtung. Ein Beitrag zur Psychophysik (1907), or Climate and Poetics: A Contribution to Psychophysics, where he explains his understanding of the relationship between ethnicity and sexuality. Bisexuality, in this context, refers to a combination of a masculine and feminine disposition, rather than the sexual orientation people understand it to be today. Medical sexology would call this “psychic hermaphroditism”, but for Kupffer, this bisexuality would be represented in the aesthetic depictions of idealised androgynous male bodies.

- Ticino is a canton in Switzerland that includes the municipality of Ascona, where Elisàr von Kupffer’s cyclorama painting can be seen today at the Elisarion Pavilion in Monte Verità. His former residence in Minusio, the Sanctum Artis Elisarion, has been turned into the Elisarion Cultural Centre and Museum.

- See also Ben Miller on “Rejecting the Klarwelt: How Elisàr von Kupffer Complicates Queer History”: https://benwritesthings.com/rejecting-the-klarwelt-how-elisar-von-kupffer-complicates-queer-history-nsdoku-munchen/.

- The terms “Homosexual” and “Heterosexual” in German are both coined by Hungarian journalist Károly Mária Kertbeny (born Karl Maria Benkert), who published pamphlets arguing against the penal code that criminalised male same-sex intercourse. The vocabulary was popularised by sexologists like Richard von Krafft-Ebing (author of the influential Psychopathia Sexualis (1886)) and it would come to take precedence over other concepts, such as Karl Heinrich Ulrichs’s Urning*in and Dioning*in inspired by Plato’s Symposium. Interestingly, the term “heterosexual” also carried the connotation of a pathological condition and only later began to be used to denote a “normal” sexual disposition.

- “Per scientiam ad justitiam” (Lat.)

- Der Eigene: ein Blatt für männliche Kultur (1896-1932) is considered to be one of the first gay journals in the world. Humboldt University of Berlin has digitised its copies: https://www.digi-hub.de/viewer/toc/BV042579260/1/.

- Estonian newspapers were interested in the relationship between homosexuality and the “Great Men” of history, as well. See Uudisleht, nr. 68, 28 August 1929: “Geenius-hull. Enamus geeniustest – homoseksualistid. – Missugused olid nad inimestena.” (“Genius-lunatic. Most geniuses – homosexualists. What were they like as people.”), using examples of Alexander the Great, Byron, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci among others.

- The title of Stirner’s book Der Einzige und sein Eigentum (1844), or The Unique and its Property, is also the inspiration behind the journal Der Eigene.

- See more from Vahur Aabrams’s entry in the Digital Text Repository for Older Estonian Literature https://utlib.ut.ee/eeva/index.php?lang=en&do=autor&aid=979

- 3000 Jahre Bolschewismus (1919). On Kupffer’s other writing concerning the revolutions, see also Hannes Vinnal’s “Elisàr von Kupfferi elu ja looming Balti mõisakultuuri loojangu valguses” in Kalevi alt välja (2022): https://www.lgbt.ee/raamat-kalevi-alt-valja.

- Judeo-Bolshevism is a conspiracy theory central to Nazi antisemitism that believes that the communist movements and the revolutions at the beginning of the century were controlled by Jewish people attempting to destroy the “Western civilisation”.

- Sociologist and author of Männerphantasien (1977), or Male Fantasies, that discusses the fantasies of men at the front of the rise of Nazism in Germany and the socialisation of fascist male soldiers.

- Giovanni Antonio Bazzi, Italian painter from the Renaissance period. Elisàr von Kupffer wrote and published an article about the artist in the Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen (or Yearbook of Intermediate Sexual Types), an annual journal of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, where he argued that in Il Sodoma’s works an ideal masculinity is created by combining power and grace, the strength of Ares and the beauty of Aphrodite together in the androgynous figure of the Araphrodite. See Damien Delille on “Queer Mysticism: Elisàr von Kupffer and the Androgynous Reform of Art”: https://shs.hal.science/halshs-01796704 (translation into Estonian in Vikerkaar 3/2024).

- Wincklemann’s most famous work Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (1764), or History of the Art of Antiquity, plays an important role in the development of European fascination with ancient Greek art in the 18th century.

- Historian and author of The Queer Art of History: Queer Kinship After Fascism (2023) that looks at postwar German history through a perspective of intersectionality and argues that kinship as a practice can resurrect a more radical potential of queer politics.